by Black Life, Stereoviews

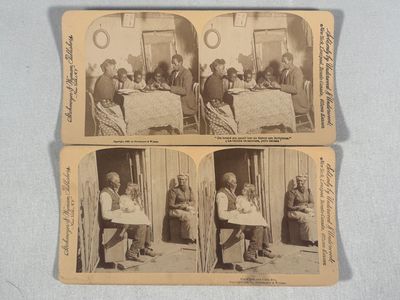

African Americans in cotton fields, cabins, and domestic scenes in the post-Reconstruction South depicted in 9 early 20th century steroeviews. Strohmeyer & Wyman, Keystone View Co., Underwood & Underwood, 1899–1905. Group of 9 stereoscopic photographs mounted on standard stereoview cards, most measuring 3.5" x 7", including one hand-colored example. With publisher and photographer details printed in margins. All images depict African American subjects in the rural South and are steeped in the racial caricature, social hierarchy, and economic marginalization of the era.

Two images are titled Cotton is King, including one hand-colored version and one sepia, both depicting African American laborers in a Georgia cotton field. The composition centers Black men, women, and children bent at work among dense cotton plants, with one woman lifting a basket as others fill sacks at their feet. These images reinforce the Southern agrarian mythology of the "happy worker in the cotton field" that white publishers marketed aggressively to postbellum audiences nostalgic for the antebellum South. Other stereoviews reinforce plantation-era tropes. “Uncle Tom and Little Eva” (copyright 1899) portrays an elderly Black man seated at a cabin doorway with a white child in his lap, a direct visual echo of the sentimental scenes from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In “Blackberries and Milk,” a smiling Black woman serves a white child inside a log cabin—again evoking the “mammy” stereotype of cheerful domestic servitude. The image captioned “De breed am small but de flavor am delicious” (1899) shows an entire Black family around a modest table, head bowed in prayer, reinforcing the idea of contented humility. Several cards in the set employ vernacular “plantation dialect” as captions, such as “We Mary! Sut 'siah! I married young, but I be de mother ob twins”, playing to racist humor and presumed backwardness. Even when children or family scenes are the focus, the visual and textual messaging consistently underscores a narrative of simplicity, humor, and submission. Also includes one image which seems to portray a white woman in blackface buying hosiery. This collection of early 20th-century stereoviews offers a rare but problematic lens into African American life as imagined—and commodified—by white photographic publishers during the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow era. Produced between the late 1890s and early 1900s by firms such as Strohmeyer & Wyman, Underwood & Underwood, and Keystone View Co., these cards formed part of mass-market stereoscopic sets marketed to white consumers, both as educational tools and as exoticized “ethnic types.” While visually rich and technically well executed, the photographs overwhelmingly reflect a paternalistic and stereotyped portrayal of Black life, designed to affirm white supremacist narratives of racial difference, docility, and contentment in labor.

Taken together, these stereoviews reflect the dominant racial ideology of the time: that Black Americans, though free, remained culturally and intellectually inferior and socially marginal. These images circulated widely in educational and entertainment sets, reinforcing these ideas in white American households. Simultaneously, they erase the political reality of the era—marked by disenfranchisement, racial terror, economic deprivation, and the brutal enforcement of Jim Crow laws. By selectively presenting African American life through the lens of domesticity, childlike innocence, and rustic humor, the images work as tools of ideological containment and erasure. Prints generally clean and sharp with excellent stereoscopic clarity. One card with a corner crease; others with minor edge wear or rubbing. All remain in Very good condition overall. (Inventory #: 21780)

Two images are titled Cotton is King, including one hand-colored version and one sepia, both depicting African American laborers in a Georgia cotton field. The composition centers Black men, women, and children bent at work among dense cotton plants, with one woman lifting a basket as others fill sacks at their feet. These images reinforce the Southern agrarian mythology of the "happy worker in the cotton field" that white publishers marketed aggressively to postbellum audiences nostalgic for the antebellum South. Other stereoviews reinforce plantation-era tropes. “Uncle Tom and Little Eva” (copyright 1899) portrays an elderly Black man seated at a cabin doorway with a white child in his lap, a direct visual echo of the sentimental scenes from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In “Blackberries and Milk,” a smiling Black woman serves a white child inside a log cabin—again evoking the “mammy” stereotype of cheerful domestic servitude. The image captioned “De breed am small but de flavor am delicious” (1899) shows an entire Black family around a modest table, head bowed in prayer, reinforcing the idea of contented humility. Several cards in the set employ vernacular “plantation dialect” as captions, such as “We Mary! Sut 'siah! I married young, but I be de mother ob twins”, playing to racist humor and presumed backwardness. Even when children or family scenes are the focus, the visual and textual messaging consistently underscores a narrative of simplicity, humor, and submission. Also includes one image which seems to portray a white woman in blackface buying hosiery. This collection of early 20th-century stereoviews offers a rare but problematic lens into African American life as imagined—and commodified—by white photographic publishers during the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow era. Produced between the late 1890s and early 1900s by firms such as Strohmeyer & Wyman, Underwood & Underwood, and Keystone View Co., these cards formed part of mass-market stereoscopic sets marketed to white consumers, both as educational tools and as exoticized “ethnic types.” While visually rich and technically well executed, the photographs overwhelmingly reflect a paternalistic and stereotyped portrayal of Black life, designed to affirm white supremacist narratives of racial difference, docility, and contentment in labor.

Taken together, these stereoviews reflect the dominant racial ideology of the time: that Black Americans, though free, remained culturally and intellectually inferior and socially marginal. These images circulated widely in educational and entertainment sets, reinforcing these ideas in white American households. Simultaneously, they erase the political reality of the era—marked by disenfranchisement, racial terror, economic deprivation, and the brutal enforcement of Jim Crow laws. By selectively presenting African American life through the lens of domesticity, childlike innocence, and rustic humor, the images work as tools of ideological containment and erasure. Prints generally clean and sharp with excellent stereoscopic clarity. One card with a corner crease; others with minor edge wear or rubbing. All remain in Very good condition overall. (Inventory #: 21780)