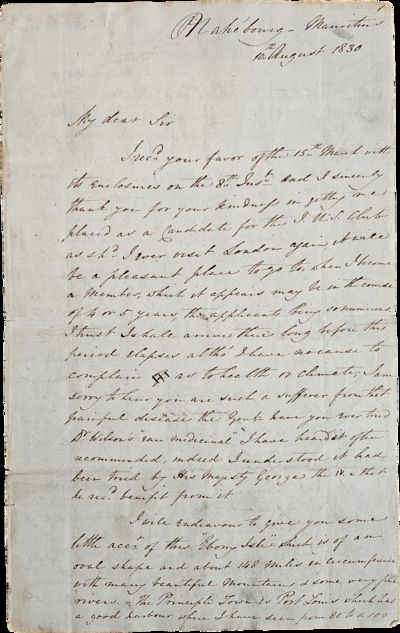

Single unsigned fourteen-page letter measuring 8 x 12 ¾ inches

1830 · Mahébourg, Mauritius

by [British Empire – Mauritius – Slavery] Unknown Author

Mahébourg, Mauritius, 1830. Single unsigned fourteen-page letter measuring 8 x 12 ¾ inches. Folded with some stains and pencil marks. Overall near fine.. In 1830, Mauritius was a British colony, captured from the French in 1810 during the Napoleonic Wars. It was originally a Dutch colony, and the Dutch had introduced enslaved labor to the islands. Enslaved people were imported from Madagascar, India, and Southeast Asia to harvest the valuable ebony trees, and later to farm sugarcane. It became a French colony in 1715 and, among other provisions, the French government awarded upper-class colonists large land grants, each with twenty enslaved people to work them. Slavery was abolished in 1835 under British rule, after which the planters, still farming sugarcane, turned to indentured servant labor from India and China alongside illegal slavery.[1]

Offered here is a lengthy single letter written by an unknown author to an unknown recipient from Mahébourg in 1830, shortly before this radical change. The letter describes the lives and economic circumstances of the planters and merchants, and of the non-white population, particularly Malabar people and free and enslaved Black people.

Noting that “every inch of ground that will produce sugar cane is planted with it,” including “the former fine gardens to some of the Habitations”, the author reports on the situation for sugar planters:

“The price of sugar here is not more than 20/per Cwt. for the best quality which does not now remunerate the Planter as his expenses are becoming every day more heavy in consequence of their slaves diminishing [...] The want of Slaves induced many of the Planters to send for Chinese [?] Labourers and several hundreds were imported at a great expense, but unfortunately they did not answer, and were obliged to be reshipped for their native Country again at the charge of those who sent for them.”

The author later notes that “nearly everyone of the Planters have heavy mortgages on their Estates and [are] obliged to pay this immense Interest, which keeps them poor and will I fear ultimately ruin them”. In fact, the planters in British Mauritius had extra duties on their sugar exports compared with their Caribbean counterparts. The shopkeepers, on the other hand, “calculate on retiring with a fortune in five years,– therefore you will fancy what must be their prices + also their profits.”

Though writing from Mahébourg, the author describes the capital city of Port Louis at length, especially its Malabar Indian and free Black residents—the lives of the latter, particularly the free Black women, seem especially grim. They write:

“The Centre [of Port Louis] is inhabited by all the respectable people and many most excellent houses + buildings,– the Catholic Chapel + the English Church amongst the number. The Suburbs to the West is the part occupied by about 3000 Malabars, + called ‘Malabar Town.’ – They are dressed mostly in white, with Turbans, ear rings, +c +c and the females with ornaments in their noses and on their Toes, as they generally go bare foot. – Once a year they have what is called a ‘Yamsee’ or a festival in honor of Mehomet which lasts for about a fortnight, during which time they seem to get no sleep, a continual beating of tom toms, – jingling of bells, – carrying pagodas (which are made of various coloured paper and most richly ornamented) followed by all the population of their Caste with their faces daubed with red, white, +c and which has a most ludicrous appearance. The Suburbs to the South, is called ‘black Camp’ – the Houses being very small and poor and inhabited by all the free blacks as well as many Mulattoes. – Also a certain class of females of the population of colour – who are visited immediately on the Arrival of a Ship the Crews soon enquiring the way to the ‘Camp.’”

As regards relations between the races, the author recounts an incident that followed the 1828 abolition of the color bar, which would ostensibly give the free non-white population the same rights as the whites:

“The Theatre is a very good one, but has been closed for several months past + the Actors + Actresses gone to Bourbon in consequence of the promulgation of the act ‘causing all free people of the population of Colour’ to have the same laws – + the same privileges as the Whites,’ + fearing they ought come to the Theatre which they had hitherto been forbidden, + thereby cause disturbances, (as the French Whites detest them + wd. not sit in the same box), it was considered best to shut the Theatre which is a great loss to the Place it being the chief public amusement, and indeed the only one we have here.”

Overall a detailed letter giving insight into life in a slave colony at a time when significant changes were on the horizon. Of interest to scholars of the colonial history of Mauritius and the second wave of British colonialism.

[1] Truth and Justice Commission, Report of the Truth and Justice Commission Vol. 1 (Mauritius: Government Printing, 2011). (Inventory #: List2931)

Offered here is a lengthy single letter written by an unknown author to an unknown recipient from Mahébourg in 1830, shortly before this radical change. The letter describes the lives and economic circumstances of the planters and merchants, and of the non-white population, particularly Malabar people and free and enslaved Black people.

Noting that “every inch of ground that will produce sugar cane is planted with it,” including “the former fine gardens to some of the Habitations”, the author reports on the situation for sugar planters:

“The price of sugar here is not more than 20/per Cwt. for the best quality which does not now remunerate the Planter as his expenses are becoming every day more heavy in consequence of their slaves diminishing [...] The want of Slaves induced many of the Planters to send for Chinese [?] Labourers and several hundreds were imported at a great expense, but unfortunately they did not answer, and were obliged to be reshipped for their native Country again at the charge of those who sent for them.”

The author later notes that “nearly everyone of the Planters have heavy mortgages on their Estates and [are] obliged to pay this immense Interest, which keeps them poor and will I fear ultimately ruin them”. In fact, the planters in British Mauritius had extra duties on their sugar exports compared with their Caribbean counterparts. The shopkeepers, on the other hand, “calculate on retiring with a fortune in five years,– therefore you will fancy what must be their prices + also their profits.”

Though writing from Mahébourg, the author describes the capital city of Port Louis at length, especially its Malabar Indian and free Black residents—the lives of the latter, particularly the free Black women, seem especially grim. They write:

“The Centre [of Port Louis] is inhabited by all the respectable people and many most excellent houses + buildings,– the Catholic Chapel + the English Church amongst the number. The Suburbs to the West is the part occupied by about 3000 Malabars, + called ‘Malabar Town.’ – They are dressed mostly in white, with Turbans, ear rings, +c +c and the females with ornaments in their noses and on their Toes, as they generally go bare foot. – Once a year they have what is called a ‘Yamsee’ or a festival in honor of Mehomet which lasts for about a fortnight, during which time they seem to get no sleep, a continual beating of tom toms, – jingling of bells, – carrying pagodas (which are made of various coloured paper and most richly ornamented) followed by all the population of their Caste with their faces daubed with red, white, +c and which has a most ludicrous appearance. The Suburbs to the South, is called ‘black Camp’ – the Houses being very small and poor and inhabited by all the free blacks as well as many Mulattoes. – Also a certain class of females of the population of colour – who are visited immediately on the Arrival of a Ship the Crews soon enquiring the way to the ‘Camp.’”

As regards relations between the races, the author recounts an incident that followed the 1828 abolition of the color bar, which would ostensibly give the free non-white population the same rights as the whites:

“The Theatre is a very good one, but has been closed for several months past + the Actors + Actresses gone to Bourbon in consequence of the promulgation of the act ‘causing all free people of the population of Colour’ to have the same laws – + the same privileges as the Whites,’ + fearing they ought come to the Theatre which they had hitherto been forbidden, + thereby cause disturbances, (as the French Whites detest them + wd. not sit in the same box), it was considered best to shut the Theatre which is a great loss to the Place it being the chief public amusement, and indeed the only one we have here.”

Overall a detailed letter giving insight into life in a slave colony at a time when significant changes were on the horizon. Of interest to scholars of the colonial history of Mauritius and the second wave of British colonialism.

[1] Truth and Justice Commission, Report of the Truth and Justice Commission Vol. 1 (Mauritius: Government Printing, 2011). (Inventory #: List2931)