Hardcover

1669 · London

by Boyle, Robert (1627-91)

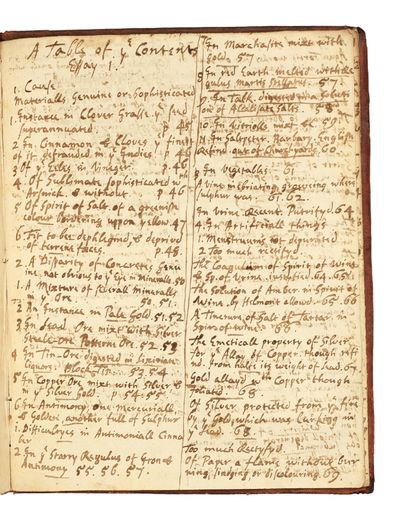

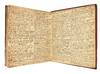

London: Printed for Henry Herringman at the Blew Anchor in the Lower Walk of the New-Exchange, 1669. SECOND EDITION, WITH ADDITIONAL MATERIAL NOT FOUND IN THE FIRST. Hardcover. Fine. Bound in contemporary blind-ruled sheep with repairs at the head of the spine and small scrapes to the boards, chips to the gilt lettering-piece on the spine. A very fine, fresh copy with generous margins. Minute worm-tracks in the gutter, never affecting the text. A few leaves with minor spotting, including the div. title to ‘The History of Fluidity.’ Leaf Pp 4 with irregular corner, not affecting the text. With an extensive contemporary (i.e. 17th c.) 6-page manuscript index on the final blank leaf and two added leaves (recto and verso). A groundbreaking work in the development of modern science (in particular the fields of chemistry and physiology) in which Boyle introduces his theory of matter. This second addition contains additional material, as described on the title.

"Boyle’s scientific associates knew him as a profound believer in the need to establish an empirically based, mechanistic theory of matter and in the possibility of establishing a scientific, rational, theoretical chemistry by means of just such a theory of matter. In 1660 he had already partially prepared a series of treatises upon both subjects, and he occupied himself for the rest of his life with the experiments and arguments furthering these beliefs. His first published declaration of his positions appeared in ‘Certain Physiological Essays’ (first edition 1661, second edition 1669)… This work made plain Boyle’s decided support for the particulate theories of matter then slowly displacing the Aristotelian view of the joint role of matter and form. Boyle was long remembered as the ‘restorer of the mechanical philosophy’ in England, and he regarded his corpuscularian philosophy as an original and useful theory of matter.”(DSB)

"Physicist, physiologist, chemist, and philosopher, Boyle was one of the great scientists and intellects of the seventeenth-century. Boyle was a leader in the movement to separate chemistry from alchemy and was among the first to define a chemical element. His interests were wide-ranging and included studies on the properties of acids and bases, hydrostatics, respiration, combustion, magnetism, electricity, and the chemical nature of blood. Although he was not formally trained as a physician, Boyle was deeply interested in the medical sciences and was made a ‘Doctor of Physick’ at Oxford in 1665. In his ‘Certain Physiological Essays’, Boyle presents a summary of his views on physical laws and their relation to human physiology. It is here that he gives the first statement of his ‘corpuscular hypothesis’, his mechanical theory of matter." (Heirs of Hippocrates)

"The importance of ‘Certain Physiological Essays’ lies in the fact that in a very real sense it was a 'prologue' to the more widely known 'Sceptical Chymist' since it continued the attack on the alchemists begun in 'New Experiments', and actually it was as much of a landmark in the history of chemistry. In the 'Essays', Boyle gives us the first clear outline of his corpuscular hypothesis concerning the nature of matter, which was to be the guiding principle of all his later chemical studies. He uses the corpuscular theory to account for the combining (or the breakdown) of 'volatile nitre' and 'fixed nitre' into saltpetre with negligible loss of weight. Corpuscles also accounted for changes of physical states of substances from solids to liquids.

“Physiology in the modern sense is illustrated in his corpuscular view of digestion (i.e. in a dog's stomach) in which solid bones were found reduced to fluids -'chyle and blood'. He concludes that something in the stomach is able quickly to reduce not only bones but 'boil'd flesh, bread, fruit, etc... to the consistency of a fluid body' thus giving recognition to the existence of the agents now designated the enzymes" (Fulton pp.20-21).

"Boyle’s first aim in ‘Certain Physiological Essays’ was to refute the older or scholastic Aristotelian view and establish the mechanical one in its place. his second aim was to show that this was best done by the use of experiment, and he devoted great care and ingenuity to devising and conducting experiments that should demonstrate the nonexistence of the supposed ‘substantial forms’ and ‘real qualities’ and the positive existence of particles whose size, shape and motion could easily and rationally account for the observed behavior and properties of matter.

"Boyle’s recognition of the complexity of the experimental approach was rare for his day. few before him had realized that empiricism required technique and the working out of methodical procedure. One reason for the tedious length of most of his treatises was his desire to describe his experiments faithfully and in such a way that others could follow. He also was always careful to describe experiments that did not succeed, a procedure that he defended in two of ‘Certain Physiological Essay’ as essential to progress in experimental philosophy. Non-empiricists might very reasonably find all this tiresomely prolix, but heuristically it was important and influential. Through his writings on his experiments, Boyle helped establish the experimental method in many branches of physics and chemistry.

"[Boyle’s] first specific publication on the corpuscular theory of matter also contains his first published accounts of chemical experiments. This is the complexly titled third essay: ‘Some specimens of an attempt to Make Chymical Experiment Useful to Illustrate the Notions of The Corpuscular Philosophy’ with the subtitle ‘A physicochemical Essay, Containing an Experiment Touching the Differing Parts and Redintegration of Salt-Petre’. The body of the essay was subsequently referred to by Boyle as ‘The Essay of Niter’. This, as he indicated, was an attempt to use a purely chemical experiment (the conversion of niter to its seemingly component parts by means of a glowing lump of charcoal and its subsequent reconstitution from the fixed and volatile parts) to demonstrate the strong probability of the existence of particles that could persist through the physical and chemical changes. Boyle recognized this as a novel approach, and also saw in it an attempt to show the chemist that the physicist’s approach, the employment of the mechanical philosophy, might be useful to chemistry; for he considered that it contributed much to an understanding of the reaction involved if one thought in terms of particles (whether simple or complex). He expressly stated in the preliminary discussion that he hoped to ‘beget a good understanding betwixt the chemists and the natural philosophers’ a lifelong desire only partially achieved." (DSB). (Inventory #: 5261)

"Boyle’s scientific associates knew him as a profound believer in the need to establish an empirically based, mechanistic theory of matter and in the possibility of establishing a scientific, rational, theoretical chemistry by means of just such a theory of matter. In 1660 he had already partially prepared a series of treatises upon both subjects, and he occupied himself for the rest of his life with the experiments and arguments furthering these beliefs. His first published declaration of his positions appeared in ‘Certain Physiological Essays’ (first edition 1661, second edition 1669)… This work made plain Boyle’s decided support for the particulate theories of matter then slowly displacing the Aristotelian view of the joint role of matter and form. Boyle was long remembered as the ‘restorer of the mechanical philosophy’ in England, and he regarded his corpuscularian philosophy as an original and useful theory of matter.”(DSB)

"Physicist, physiologist, chemist, and philosopher, Boyle was one of the great scientists and intellects of the seventeenth-century. Boyle was a leader in the movement to separate chemistry from alchemy and was among the first to define a chemical element. His interests were wide-ranging and included studies on the properties of acids and bases, hydrostatics, respiration, combustion, magnetism, electricity, and the chemical nature of blood. Although he was not formally trained as a physician, Boyle was deeply interested in the medical sciences and was made a ‘Doctor of Physick’ at Oxford in 1665. In his ‘Certain Physiological Essays’, Boyle presents a summary of his views on physical laws and their relation to human physiology. It is here that he gives the first statement of his ‘corpuscular hypothesis’, his mechanical theory of matter." (Heirs of Hippocrates)

"The importance of ‘Certain Physiological Essays’ lies in the fact that in a very real sense it was a 'prologue' to the more widely known 'Sceptical Chymist' since it continued the attack on the alchemists begun in 'New Experiments', and actually it was as much of a landmark in the history of chemistry. In the 'Essays', Boyle gives us the first clear outline of his corpuscular hypothesis concerning the nature of matter, which was to be the guiding principle of all his later chemical studies. He uses the corpuscular theory to account for the combining (or the breakdown) of 'volatile nitre' and 'fixed nitre' into saltpetre with negligible loss of weight. Corpuscles also accounted for changes of physical states of substances from solids to liquids.

“Physiology in the modern sense is illustrated in his corpuscular view of digestion (i.e. in a dog's stomach) in which solid bones were found reduced to fluids -'chyle and blood'. He concludes that something in the stomach is able quickly to reduce not only bones but 'boil'd flesh, bread, fruit, etc... to the consistency of a fluid body' thus giving recognition to the existence of the agents now designated the enzymes" (Fulton pp.20-21).

"Boyle’s first aim in ‘Certain Physiological Essays’ was to refute the older or scholastic Aristotelian view and establish the mechanical one in its place. his second aim was to show that this was best done by the use of experiment, and he devoted great care and ingenuity to devising and conducting experiments that should demonstrate the nonexistence of the supposed ‘substantial forms’ and ‘real qualities’ and the positive existence of particles whose size, shape and motion could easily and rationally account for the observed behavior and properties of matter.

"Boyle’s recognition of the complexity of the experimental approach was rare for his day. few before him had realized that empiricism required technique and the working out of methodical procedure. One reason for the tedious length of most of his treatises was his desire to describe his experiments faithfully and in such a way that others could follow. He also was always careful to describe experiments that did not succeed, a procedure that he defended in two of ‘Certain Physiological Essay’ as essential to progress in experimental philosophy. Non-empiricists might very reasonably find all this tiresomely prolix, but heuristically it was important and influential. Through his writings on his experiments, Boyle helped establish the experimental method in many branches of physics and chemistry.

"[Boyle’s] first specific publication on the corpuscular theory of matter also contains his first published accounts of chemical experiments. This is the complexly titled third essay: ‘Some specimens of an attempt to Make Chymical Experiment Useful to Illustrate the Notions of The Corpuscular Philosophy’ with the subtitle ‘A physicochemical Essay, Containing an Experiment Touching the Differing Parts and Redintegration of Salt-Petre’. The body of the essay was subsequently referred to by Boyle as ‘The Essay of Niter’. This, as he indicated, was an attempt to use a purely chemical experiment (the conversion of niter to its seemingly component parts by means of a glowing lump of charcoal and its subsequent reconstitution from the fixed and volatile parts) to demonstrate the strong probability of the existence of particles that could persist through the physical and chemical changes. Boyle recognized this as a novel approach, and also saw in it an attempt to show the chemist that the physicist’s approach, the employment of the mechanical philosophy, might be useful to chemistry; for he considered that it contributed much to an understanding of the reaction involved if one thought in terms of particles (whether simple or complex). He expressly stated in the preliminary discussion that he hoped to ‘beget a good understanding betwixt the chemists and the natural philosophers’ a lifelong desire only partially achieved." (DSB). (Inventory #: 5261)

![Bartholinus anatomy; made from the precepts of his father, and from the observations of all modern anatomists, together with his own. With one hundred fifty and three figures cut in brass, much larger and better than any have been heretofore printed in English. In four books and four manuals, answering to the said books. Book I. Of the lower belly. Book II. Of the middle venter or cavity. Book III. Of the uppermost cavities, viz. The head. Book IV. Of the limbs. The four manuals answering to the four foregoing books. Manual I. Of the veins, answering to the firs book of the lower belly. Manual II. Of the arteries, answering to the second book of the middle cavity or chest. Manual III. Of the nerves, answering to the third book of the head. Manual IV. Of the bones, answering to the fourth book of the limbs. Als [sic] two epistles of the circulation of the blood. Published by Nich. Culpeper gent. and, Abdiah Cole doctor of physick](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/170/812/1692812170.0.m.jpg)