1662 · Cologne

by BÖCKLER, Georg Andreas (1617-1687)

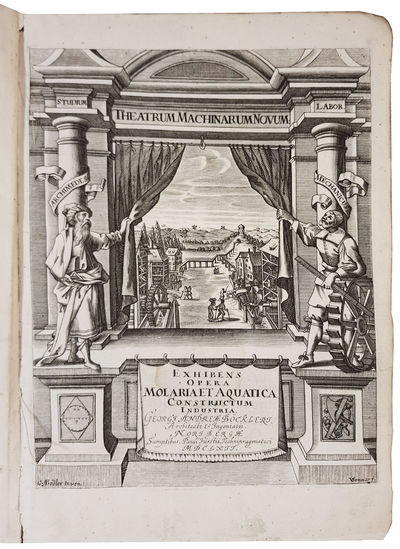

Folio (330x224 mm). Engraved title-page (Noribergae, sumptibus Pauli Furstii, technipragmatici, 1662), [10], 55, [1] pp. and [154] full-page plates engraved by Eberhard Kieser and Balthasar Schwan after drawings by Böckler himself. Collation: ¶4-¶¶1 A-G4. Contemporary stiff vellum, spine with five raised bands and ink title. On the front pastedown engraved bookplate "Otiis comitis Fontanellati &c" of Alessandro Sanvitale di Fontanellato (1731-1804), founder of the Accademia degli Erranti in Fontanellato. Some light browning and staining, but a very good, unpressed and genuine copy.

First Latin edition, in the translation by Heinrich Schmitz, of one of the most accomplished and successful 17th-century machine books. It first appeared in German at Nuremberg in 1661. The Latin edition was reprinted in 1686, the German edition in 1673, 1703 and 1705.

"It was in Germany that two of the most eminent engineering visionaries lived. The first of these was Georg Andreas Böckler who published a truly remarkable book […] called Theatrum Machinarum Novum, written and illustrated as a record of the progress of the art of engineering […] As one might gather, not just from the title page but from a knowledge of the general conditions pertaining in Germany after the Thirty Years' War, Böckler's acquaintance with machinery was restricted almost entirely to mills of one sort or another. In most of these, regardless of the motive power, he depicts the precursor of the geared transmission familiar to this day. The seventeenth-century engineers had neither the theoretical knowledge nor the technical equipment to design and shape gear-wheels which would mesh with minimum friction. In fact, friction as such, although made use of in such applications as the sack-lift in a mill, was little understood. The construction of pinions to mesh with larger gear-wheels had yet to assume the form common today. However, the problem of shifting the direction of rotation of a drive through 90° was solved by the invention of the wallower driven either by a contrite wheel (a wooden wheel with tooth pegs protruding around the circumference parallel to the axis) or by a cogwheel having teeth projecting radially around the circumference at right-angles to the axis […] The wallower comprised two discs of wood, each drilled with a matching set of concentric holes near the perimeter. The discs, usually with square centre bores to aid fixing and to transmit rotary motion, were mounted on a shaft separate by a gap of as much as the mechanism dictated, and threaded through the holes, from one disc to the next, were wooden rods. The result looked not unlike a birdcage or lantern, hence its more common name. When it was meshed with a large wheel having suitably spaced wooden pegs around either its diameter (the contrite) or its periphery (the cog), depending on whether parallel or perpendicular motion was desired, a serviceable gear train was the result. Friction, though cut efficiency drastically. All this is depicted in Böckler's Theatre of New Machines, but what is a far more striking feature of the illustrations is the constant recurrence of the germ of perpetual motion" (Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, Perpetual Motion. The History of an Obsession, Kempton IL, 2005, pp. 47-48).

The strongly inked plates show hydraulic and mechanical machines powered by intricate systems of wheels that employ water, wind, weights, animal or human power, or some combination of these. These machines include many curious inventions applicable to all trades and human activities, such as paper and grain mills, drilling machines, roasting machines, water pumps, wood saws, blowing machines, fire engines, roasting spits, and so on.

In particular, plate 5 pictures a hand mill for making ink for copperplate printing; plates 34, 36, 37, 41, 46, 47, and 59 depict mills used for grinding flour and sharpening stones, tools and knives; plate 72 shows a 'fulling mill' for pounding cloths to clean them; plates 73 and 74, considered as "the clearest delineation of the art to this date" (D. Hunter, The literature of papermaking 1390-1800, New York, 1971, p. 18), illustrate in detail paper-making by showing the linen rags being pulped with water-powered hammers, while the vatman stands ready with a mould, the coucher presses the post, and the drying sheets hang on ropes above, ready to be sized, calendared, gathered into reams, and packaged; the last plate (154) is remarkable for its depiction of a fire engine water pump made by the Nuremberg inventor Hans Hautsch in 1658, which is considered as the basis of the modern fire engine.

A comparison of Böckler's work with earlier machine books illustrates how "the focal point within the illustrations has shifted from the human to the mechanical […] Böckler shows a more developed awareness of how machines alter the status of workers was well as owners in his seventeenth-century illustrations. In one, a curtain has been drawn aside to reveal a couple at leisure eating dinner while the mill, tended by workers, operates on the floor beneath them (plate 53). Here the machine begins to determine the roles played by humans. The various illustrations portraying humans attentively watching a machine's operation indicate even further the centrality of the apparatus in the drama being portrayed" (K.J. Knoespel, Gazing on Technology: Theatrum Mechanorum and the Assimilation of Renaissance Machinery, in: "Literature and Technology", M.L. Greenberg & L. Schachterle, eds., London-Toronto, 1992, p. 110).

Born in Cronheim, Böckler was mostly active as an architect in Nuremberg. In addition to the present work he is the author of the Architectura curiosa nova (Nuremberg, 1664), which dealt with hydrodynamics applied to water-jets, fountains and wells. Böckler died in Ansbach in 1667.

VD17, 23:296774F; Macclesfield, 2195; Horblit, 132; Honeyman, 359; Ch. Singer, A History of Technology, Oxford, 1957, III, pp. 16-17; Bibliotheca de re metallica. The Herbert Clark Hoover Collection of Mining and Metallurgy, Claremont CA, 1980, no. 142 (1686 Latin edition). (Inventory #: 226)

First Latin edition, in the translation by Heinrich Schmitz, of one of the most accomplished and successful 17th-century machine books. It first appeared in German at Nuremberg in 1661. The Latin edition was reprinted in 1686, the German edition in 1673, 1703 and 1705.

"It was in Germany that two of the most eminent engineering visionaries lived. The first of these was Georg Andreas Böckler who published a truly remarkable book […] called Theatrum Machinarum Novum, written and illustrated as a record of the progress of the art of engineering […] As one might gather, not just from the title page but from a knowledge of the general conditions pertaining in Germany after the Thirty Years' War, Böckler's acquaintance with machinery was restricted almost entirely to mills of one sort or another. In most of these, regardless of the motive power, he depicts the precursor of the geared transmission familiar to this day. The seventeenth-century engineers had neither the theoretical knowledge nor the technical equipment to design and shape gear-wheels which would mesh with minimum friction. In fact, friction as such, although made use of in such applications as the sack-lift in a mill, was little understood. The construction of pinions to mesh with larger gear-wheels had yet to assume the form common today. However, the problem of shifting the direction of rotation of a drive through 90° was solved by the invention of the wallower driven either by a contrite wheel (a wooden wheel with tooth pegs protruding around the circumference parallel to the axis) or by a cogwheel having teeth projecting radially around the circumference at right-angles to the axis […] The wallower comprised two discs of wood, each drilled with a matching set of concentric holes near the perimeter. The discs, usually with square centre bores to aid fixing and to transmit rotary motion, were mounted on a shaft separate by a gap of as much as the mechanism dictated, and threaded through the holes, from one disc to the next, were wooden rods. The result looked not unlike a birdcage or lantern, hence its more common name. When it was meshed with a large wheel having suitably spaced wooden pegs around either its diameter (the contrite) or its periphery (the cog), depending on whether parallel or perpendicular motion was desired, a serviceable gear train was the result. Friction, though cut efficiency drastically. All this is depicted in Böckler's Theatre of New Machines, but what is a far more striking feature of the illustrations is the constant recurrence of the germ of perpetual motion" (Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, Perpetual Motion. The History of an Obsession, Kempton IL, 2005, pp. 47-48).

The strongly inked plates show hydraulic and mechanical machines powered by intricate systems of wheels that employ water, wind, weights, animal or human power, or some combination of these. These machines include many curious inventions applicable to all trades and human activities, such as paper and grain mills, drilling machines, roasting machines, water pumps, wood saws, blowing machines, fire engines, roasting spits, and so on.

In particular, plate 5 pictures a hand mill for making ink for copperplate printing; plates 34, 36, 37, 41, 46, 47, and 59 depict mills used for grinding flour and sharpening stones, tools and knives; plate 72 shows a 'fulling mill' for pounding cloths to clean them; plates 73 and 74, considered as "the clearest delineation of the art to this date" (D. Hunter, The literature of papermaking 1390-1800, New York, 1971, p. 18), illustrate in detail paper-making by showing the linen rags being pulped with water-powered hammers, while the vatman stands ready with a mould, the coucher presses the post, and the drying sheets hang on ropes above, ready to be sized, calendared, gathered into reams, and packaged; the last plate (154) is remarkable for its depiction of a fire engine water pump made by the Nuremberg inventor Hans Hautsch in 1658, which is considered as the basis of the modern fire engine.

A comparison of Böckler's work with earlier machine books illustrates how "the focal point within the illustrations has shifted from the human to the mechanical […] Böckler shows a more developed awareness of how machines alter the status of workers was well as owners in his seventeenth-century illustrations. In one, a curtain has been drawn aside to reveal a couple at leisure eating dinner while the mill, tended by workers, operates on the floor beneath them (plate 53). Here the machine begins to determine the roles played by humans. The various illustrations portraying humans attentively watching a machine's operation indicate even further the centrality of the apparatus in the drama being portrayed" (K.J. Knoespel, Gazing on Technology: Theatrum Mechanorum and the Assimilation of Renaissance Machinery, in: "Literature and Technology", M.L. Greenberg & L. Schachterle, eds., London-Toronto, 1992, p. 110).

Born in Cronheim, Böckler was mostly active as an architect in Nuremberg. In addition to the present work he is the author of the Architectura curiosa nova (Nuremberg, 1664), which dealt with hydrodynamics applied to water-jets, fountains and wells. Böckler died in Ansbach in 1667.

VD17, 23:296774F; Macclesfield, 2195; Horblit, 132; Honeyman, 359; Ch. Singer, A History of Technology, Oxford, 1957, III, pp. 16-17; Bibliotheca de re metallica. The Herbert Clark Hoover Collection of Mining and Metallurgy, Claremont CA, 1980, no. 142 (1686 Latin edition). (Inventory #: 226)

![Publii Virgilii Maronis Opera, cum Servii commentariis, exactiori cura suae integritati restitutis. Habes item Io. Pierii Valeriani Castigationes, & Verietates lectionis in totum Virgilium […] Accedunt praeterea in omnia Virgili opera Stephani Doleti Annotatiunculae, Ioca obscura elucidantes, ac doctissimi Commentarii vicem fingentes. Additis novis quibusdam Io. Musonii viri quam eruditissimi lucubrationibus, quas inspexisse haud quaquam pigebit: [...]](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/001/648/1692648001.0.m.jpg)