Hardcover

1630 · Bracciano

by Scheiner, Christoph (1573 or 1575 – 1650)

Bracciano: [Privately Printed by] Andreas Phaeus, 1626 to, 1630. SOLE EDITION. Hardcover. Fine. An excellent copy. Bound in contemporary vellum, lacking ties (a few wormholes to the lower cover, small puncture and a little rumpling along the fore-edge of the upper cover.) Complete with the errata leaf and blanks F4, R6 & 4I6 (b3 bound after c2, few small tears, a some scattered toning and foxing, a few inconsequential blemishes). With an early German manuscript shelf label – “M.W.” (19th-century bookplate with coronet). Illustrated with an engraved allegorical frontispiece, fine engraved portrait of Paolo Giordano Orsini Duke of Bracciano with dedication, engraved vignette on printed title, & many fine engraved illustrations in the text (many full-page) depicting the author’s observations of sunspots, his observational platform (with his assistants busily working), his telescopes and helioscopes of his own design. Scheiner’s greatest work. This magnificent book, along with Hevelius’ lunar atlas, “Selenographia”, is one of the two most richly and superbly illustrated astronomy book published in the first half of the 17th century. It describes and depicts Scheiner’s observations of sunspots and showcases his instruments, including his Keplerian telescope and his helioscope.

In 1611, Scheiner constructed a telescope with which he began to make astronomical observations, and in March of that year, he detected the presence of spots on the sun. Scheiner’s claim to the discovery of sun spots, independently of Galileo, was the origin of one of the most famous and heated controversies in the history of science. This book contains the summation of Scheiner’s observations of the sun, the fruit of many years of observation and study. He confirmed his method and criticized Galileo for failing to mention the inclination of the axis of rotation to the plane of the ecliptic. Yet he finally agreed with Galileo that sunspots are on the Sun's surface or in its atmosphere (rather than satellites), that they are often generated and perish there, and that the Sun is therefore not perfect. Scheiner further advocated a fluid heavens (against the Aristotelian solid spheres), and he pioneered new ways of representing the motions of spots across the Sun's face. Because shortly after the appearance of Rosa Ursina sunspot activity decreased drastically (the so-called Maunder Minimum, ca. 1645-1710), his work was not superseded until well into the eighteenth century.

Scheiner was responsible for many advances and innovations in the design of telescopes and related instruments. Of great importance is Scheiner’s creation of a special helioscope, described here, the first Keplerian telescope in use, consisting of two convex lenses; it was also the first to use colored glass in the eyepiece (Kepler himself had only considered the telescope theoretically.) Scheiner is also known for having invented the pantograph and for establishing the retina as the seat of vision. The quality of the engravings in this book is exceptional. Not only the complete instruments but also their component parts, lenses, fittings, etc. are depicted in these engravings.

Rosa Ursina sive Sol was costly to produce. Scheiner originally sought the support of Cardinal Alessandro Orsini (1592-1626), who was close to the Jesuits, and after Alessandro’s death, that of his brother, Paolo Giordano II, Duke of Bracciano, a great patron of astronomy. Rosa Ursina sive Sol was thus published at Bracciano on the Duke’s private press, though over several years (1626-30) due to financial difficulties. The book, starting with its title, is replete with references to the Orsini family whose heraldry included the rose and the bear (orsus = ursus = bear). Given the strained relations with Paolo Giordano II, who was unwilling to pay for the book, these references to the Orsini family quickly became obsolete.

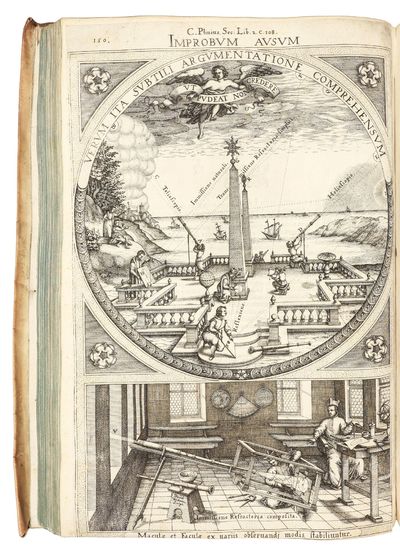

Depicting the Astronomical Observatory and Methods of Observing Sunspots:

On page 150 there is a remarkable, full-page engraving with two scenes of astronomers at work. The first shows a viewing terrace, outfitted with two obelisks and a number of figures using astronomical instruments, including a helioscope and a telescope. Three figures may be identified as Jesuits from their distinctive birettas. One is at the foot of the obelisk measuring the position of the reflected sunspot against a plumb line (at M) with a compass. The second image, an interior scene, shows Scheiner and his assistant at work in his study, which has astrolabes and a quadrant on the walls.

This plate illustrates seven methods of observing sunspots:

1) the simplest and most natural way of observation is to let the Sun (at F) shine through a bare opening of a ball (at G) into a dark place where a paper is held perpendicularly and on which a figure is formed (at H).

2) another simple form of observation is to let the Sun (at Q) shine through a convex glass (at R) onto a chart (at S).

3) the simplest and most natural way of observation is with the naked eye (at P) when the Sun is at the horizon (at I).

4) observation of the Sun (at E) through a helioscope (at D).

5) observation of the Sun (at B) behind a cloud (at C) through a telescope (at A).

6) observation of the Sun (at I) by a reflection (at LN) by a plane mirror (at K). This is a method that Scheiner initially used at Ingolstadt.

7) observation of the Sun where its ray (V) through a helioscopic tube (at X) is projected onto paper in the circle Y contained in the perimeter cfdg. This method is described as ‘the most excellent, the most secure and the easiest’ method of observation which Scheiner used at Ingolstadt from 1612, as well as at Rome.

The Christogram ‘IHS’ adopted by the Jesuits as their emblem, may be seen at the top of one of the obelisks, and the rose of the Orsini family may be found on the edge of the roundel and elsewhere. On the side of a stool on which a telescope and sundial rest, is the signature of the engraver, Daniel Widman. The quotation at the top of the image is from Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis historia II.112, where Eratosthenes’s estimate of the circumference of Earth is described as ‘an audacious venture, but achieved by such subtle reasoning that one is ashamed to be sceptical.'. (Inventory #: 5226)

In 1611, Scheiner constructed a telescope with which he began to make astronomical observations, and in March of that year, he detected the presence of spots on the sun. Scheiner’s claim to the discovery of sun spots, independently of Galileo, was the origin of one of the most famous and heated controversies in the history of science. This book contains the summation of Scheiner’s observations of the sun, the fruit of many years of observation and study. He confirmed his method and criticized Galileo for failing to mention the inclination of the axis of rotation to the plane of the ecliptic. Yet he finally agreed with Galileo that sunspots are on the Sun's surface or in its atmosphere (rather than satellites), that they are often generated and perish there, and that the Sun is therefore not perfect. Scheiner further advocated a fluid heavens (against the Aristotelian solid spheres), and he pioneered new ways of representing the motions of spots across the Sun's face. Because shortly after the appearance of Rosa Ursina sunspot activity decreased drastically (the so-called Maunder Minimum, ca. 1645-1710), his work was not superseded until well into the eighteenth century.

Scheiner was responsible for many advances and innovations in the design of telescopes and related instruments. Of great importance is Scheiner’s creation of a special helioscope, described here, the first Keplerian telescope in use, consisting of two convex lenses; it was also the first to use colored glass in the eyepiece (Kepler himself had only considered the telescope theoretically.) Scheiner is also known for having invented the pantograph and for establishing the retina as the seat of vision. The quality of the engravings in this book is exceptional. Not only the complete instruments but also their component parts, lenses, fittings, etc. are depicted in these engravings.

Rosa Ursina sive Sol was costly to produce. Scheiner originally sought the support of Cardinal Alessandro Orsini (1592-1626), who was close to the Jesuits, and after Alessandro’s death, that of his brother, Paolo Giordano II, Duke of Bracciano, a great patron of astronomy. Rosa Ursina sive Sol was thus published at Bracciano on the Duke’s private press, though over several years (1626-30) due to financial difficulties. The book, starting with its title, is replete with references to the Orsini family whose heraldry included the rose and the bear (orsus = ursus = bear). Given the strained relations with Paolo Giordano II, who was unwilling to pay for the book, these references to the Orsini family quickly became obsolete.

Depicting the Astronomical Observatory and Methods of Observing Sunspots:

On page 150 there is a remarkable, full-page engraving with two scenes of astronomers at work. The first shows a viewing terrace, outfitted with two obelisks and a number of figures using astronomical instruments, including a helioscope and a telescope. Three figures may be identified as Jesuits from their distinctive birettas. One is at the foot of the obelisk measuring the position of the reflected sunspot against a plumb line (at M) with a compass. The second image, an interior scene, shows Scheiner and his assistant at work in his study, which has astrolabes and a quadrant on the walls.

This plate illustrates seven methods of observing sunspots:

1) the simplest and most natural way of observation is to let the Sun (at F) shine through a bare opening of a ball (at G) into a dark place where a paper is held perpendicularly and on which a figure is formed (at H).

2) another simple form of observation is to let the Sun (at Q) shine through a convex glass (at R) onto a chart (at S).

3) the simplest and most natural way of observation is with the naked eye (at P) when the Sun is at the horizon (at I).

4) observation of the Sun (at E) through a helioscope (at D).

5) observation of the Sun (at B) behind a cloud (at C) through a telescope (at A).

6) observation of the Sun (at I) by a reflection (at LN) by a plane mirror (at K). This is a method that Scheiner initially used at Ingolstadt.

7) observation of the Sun where its ray (V) through a helioscopic tube (at X) is projected onto paper in the circle Y contained in the perimeter cfdg. This method is described as ‘the most excellent, the most secure and the easiest’ method of observation which Scheiner used at Ingolstadt from 1612, as well as at Rome.

The Christogram ‘IHS’ adopted by the Jesuits as their emblem, may be seen at the top of one of the obelisks, and the rose of the Orsini family may be found on the edge of the roundel and elsewhere. On the side of a stool on which a telescope and sundial rest, is the signature of the engraver, Daniel Widman. The quotation at the top of the image is from Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis historia II.112, where Eratosthenes’s estimate of the circumference of Earth is described as ‘an audacious venture, but achieved by such subtle reasoning that one is ashamed to be sceptical.'. (Inventory #: 5226)

![Bartholinus anatomy; made from the precepts of his father, and from the observations of all modern anatomists, together with his own. With one hundred fifty and three figures cut in brass, much larger and better than any have been heretofore printed in English. In four books and four manuals, answering to the said books. Book I. Of the lower belly. Book II. Of the middle venter or cavity. Book III. Of the uppermost cavities, viz. The head. Book IV. Of the limbs. The four manuals answering to the four foregoing books. Manual I. Of the veins, answering to the firs book of the lower belly. Manual II. Of the arteries, answering to the second book of the middle cavity or chest. Manual III. Of the nerves, answering to the third book of the head. Manual IV. Of the bones, answering to the fourth book of the limbs. Als [sic] two epistles of the circulation of the blood. Published by Nich. Culpeper gent. and, Abdiah Cole doctor of physick](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/170/812/1692812170.0.m.jpg)