signed first edition custom folder

1946 · Brussels, Belgium

by MAGRITTE, RENÉ

Brussels, Belgium: np, 1946. custom folder. Fine. A MAJOR LETTER BY MAGRITTE DEFINING HIS ARTISTIC INTENTIONS AND HIS RELATIONHIP TO SURREALISM. In the early 1940s, Magritte entered his ‘Renoir period,’ during which he sought to bring pleasure into what he saw as an increasingly darkened world, marred by the rise of fascism and the brutality of World War II. In the interwar period, Magritte had played a pivotal role in the rise of Surrealism— notably in works like The Treachery of Images and The Lover— but by the end of World War II, he grew to believe that the, “confusion and panic that Surrealism wanted to create in order to bring everything into question were achieved much better by the Nazi idiots than us.” As a result, “in the face of general pessimism, [Magritte] now urge[d] a search for joy, for pleasure” [Danchev].

Significantly, Magritte associated his art with his own political anti-fascism. Magritte believed Surrealism and Nazism had both aimed to evoke a similar sensation of disorder in the experiencer (although to different ends). Still, to Magritte, a rejection of fascism required not only anti-fascist messaging but also methods that evoked joy and pleasure in the contestation of violence and disorder. Magritte associated this task with his ‘Renoir’ style [Danchev].

In this letter to Surrealist poet Joë Bousquet— the owner of an estate in Carcassonne which had served as a destination for cultural elites such as Breton, Éluard, Gide, et al.— Magritte speaks of his intentions in this new style:

“The austerity that once defined my style has receded, now more subtle and essential, able to withstand the glare of the midday sun.”

Magritte associates the intention of his art with the simple pleasure of eating a fruit:

“By consuming a simple fruit, we let the sunshine enter our bodies. This notion resonates profoundly with the sentiment that imbues one of my latest works, La Vie privée— a painting in which a window overlooking a sun-drenched landscape is nestled within the form of a nude woman.”

Magritte’s Renoir period cannot be simplified only to the pursuit of joy. He situated his works in conversation with what he characterized as prevailing Surrealist currents of artistic violence and chaos:

“‘Surrealist’ painting, as practiced by numerous artists, has become overwhelming: severed hands abound, blood flows freely, and the inventions are ingeniously disturbing. These artists seem blind, inhabiting a dusty surrealist museum where even a bouquet of real flowers would scandalize. My proposal is to clear this atmosphere, despite the inevitable challenges. Addressing these questions are Le Savoir-Vivre, I say, among other things:

I hate both my own past and that of others

I cherish the laughter of young children running free.”

Magritte derides Surrealism not because he believes it dull—he labels it “ingenious”—but because, in a Europe that had just tipped into extreme chaos, he saw Surrealism as redundant: neither challenging nor clearing the cultural imagination. Although exact intentions are up to scholarly interpretation, Magritte draws connections between historical interpretation as associated with the language of ‘progress,’ and the overwhelming chaos of Surrealist art, writing [Danchev]:

“There’s no such thing as progress — there are good and bad things that are replaced, succeeded and transformed.

There’s nothing to learn — there are things you need to know in order to use them.”

This 1946 letter to Bousquet is deeply interested in contesting prevailing cultural norms— whether they be a style of Surrealism Magritte himself helped to create, or language of ‘progress’ in a Europe returning from near fascism.

Importantly, this letter also contains what might be understood as an interpersonal argument. Joë Bousquet himself was a poet and a Surrealist (an original signatory of André Breton’s manifesto). Although Bousquet’s work received little renown during his own life—in part because of his disorienting blend of Surrealist and existentialist prose—today, Bousquet is celebrated. His works were rediscovered in the 1960s by the likes of Simone Weil, Paul Éluard, and Max Ernst. Bousquet’s prose was, in many ways, allied with the disorder of Surrealism—his stories have no plots, and the characters usually appear and disappear by the end of the story. In this way, as Magritte situates this letter as a critique of an artistic movement, he also challenges Bousquet’s own writing.

This letter makes explicit the cultural critique embedded in Magritte’s art— the ethos that made him much more than just “a Surrealist,” but a revolutionary artist and thinker, committed to deconstructing the world around him.

The text (in translation from the original French) reads in full:

“Jette-Brussels, 3rd August 1946

135 rue ESSEGHEM

My dear friend,

Since my departure from Carcassonne, I have written to you on numerous occasions, yet I fear only a handful of my letters have reached you.

Your own missives have been sparse, leaving me with only vague tidings, and your most recent letter has left me unsettled. I await with great impatience the books you promised to send. Your sentiment, expressed long ago, set me on the path I now tread. You spoke of how, by consuming a simple fruit, we let the sunshine enter our bodies.

This notion resonates profoundly with the sentiment that imbues one of my latest works, "La Vie privée" — a painting in which a window overlooking a sun-drenched landscape is nestled within the form of a nude woman. This piece encapsulates the revolution in my art — a sentimental revolution, first and foremost, aimed at replacing anxiety with joy and the warmth of sunshine. The austerity that once defined my style has receded, now more subtle and essential, able to withstand the glare of the midday sun. Is this a demonstration (in the full light of day, we must ponder) of the "results" of a desire to overturn the established order, a desire that the war allowed "men" to indulge for four long years? During that time, I came to believe that these "men" possessed greater means than we did to sow panic, despair, and anxiety from which there was no escape. Yet, paradoxically, these same "men" were utterly bereft of the power to charm. It occurred to me that it is we who hold that power, and if we seek to achieve effects as grandiose as those of evil, but this time in service of good (by which I mean: that which enchants, that which intoxicates), there is much to be reconsidered, discarded, and discovered. To illustrate this notion, I offer two examples: Gallimard's "Série Noire" publishes adventure novels, one of which, "Pas d’orchidées pour Miss Blandish," reaches a certain pinnacle of horror and sickness. I propose the exact opposite, and I believe we have glimpsed this in works such as "Alice in Wonderland" and the tales of Perrault and d’Aulnoy. We must now strive to attain the same power in the realm of the charming and delightful as we do (with such ease) in the realm of the dark and sickening.

"Surrealist” painting, as practiced by numerous artists, has become overwhelming: severed hands abound, blood flows freely, and the inventions are ingeniously disturbing. These artists seem blind, inhabiting a dusty surrealist museum where even a bouquet of real flowers would scandalize. My proposal is to clear this atmosphere, despite the inevitable challenges. Addressing these questions re Le Savoir-Vivre, I say, among other things:

I hate both my own past and that of others

I cherish the laughter of young children running free.”

which illuminates my current sentiments and desires. I am eager to hear your thoughts on these matters. 'Le Savoir-Vivre' is soon to be printed, and I required responses by June 30th. However, timely replies could still be accommodated for publication. (Given the limited space available, please keep your contributions concise). Enclosed is a questionnaire for your convenience.

On the topic of purchases, I enclose a list of items with prices. I'm also sending you a small collection by a young poet – I don't know if you've already received it – and a few illustrated postcards.

I sometimes toy with the idea of surprising you one day, which doesn't seem that utopian to me.

“There’s no such thing as progress — there are good and bad things that are replaced, succeeded and transformed.

There’s nothing to learn — there are things you need to know in order to use them.”

See you soon, I hope, and all the best

Magritte [Signed]

P.S. During the war, did you not receive:

Les Images Défendues by Paul Nougé

Magritte – preface by Marien"

[Translation by Daniele Tort Moloney.]

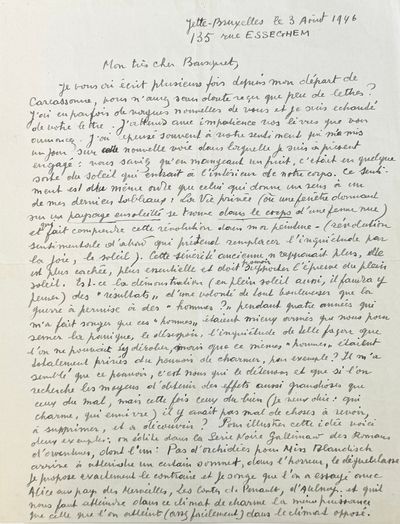

Autograph Letter Signed [ALS]. Two pages on two sheets (approx. 8.25 x 10.5 in per sheet). Housed in custom presentation folder. Usual mailing folds; fine condition.

AN EXCEPTIONALLY REVEALING AND IMPORTANT LETTER GIVING INSIGHT INTO MAGRITTE'S ART.

References:

- Danchev, Alex. Magritte: A Life. Pantheon, 2021.

- “Joë Bousquet.” EBSCO Research Starters. (Inventory #: 2975)

Significantly, Magritte associated his art with his own political anti-fascism. Magritte believed Surrealism and Nazism had both aimed to evoke a similar sensation of disorder in the experiencer (although to different ends). Still, to Magritte, a rejection of fascism required not only anti-fascist messaging but also methods that evoked joy and pleasure in the contestation of violence and disorder. Magritte associated this task with his ‘Renoir’ style [Danchev].

In this letter to Surrealist poet Joë Bousquet— the owner of an estate in Carcassonne which had served as a destination for cultural elites such as Breton, Éluard, Gide, et al.— Magritte speaks of his intentions in this new style:

“The austerity that once defined my style has receded, now more subtle and essential, able to withstand the glare of the midday sun.”

Magritte associates the intention of his art with the simple pleasure of eating a fruit:

“By consuming a simple fruit, we let the sunshine enter our bodies. This notion resonates profoundly with the sentiment that imbues one of my latest works, La Vie privée— a painting in which a window overlooking a sun-drenched landscape is nestled within the form of a nude woman.”

Magritte’s Renoir period cannot be simplified only to the pursuit of joy. He situated his works in conversation with what he characterized as prevailing Surrealist currents of artistic violence and chaos:

“‘Surrealist’ painting, as practiced by numerous artists, has become overwhelming: severed hands abound, blood flows freely, and the inventions are ingeniously disturbing. These artists seem blind, inhabiting a dusty surrealist museum where even a bouquet of real flowers would scandalize. My proposal is to clear this atmosphere, despite the inevitable challenges. Addressing these questions are Le Savoir-Vivre, I say, among other things:

I hate both my own past and that of others

I cherish the laughter of young children running free.”

Magritte derides Surrealism not because he believes it dull—he labels it “ingenious”—but because, in a Europe that had just tipped into extreme chaos, he saw Surrealism as redundant: neither challenging nor clearing the cultural imagination. Although exact intentions are up to scholarly interpretation, Magritte draws connections between historical interpretation as associated with the language of ‘progress,’ and the overwhelming chaos of Surrealist art, writing [Danchev]:

“There’s no such thing as progress — there are good and bad things that are replaced, succeeded and transformed.

There’s nothing to learn — there are things you need to know in order to use them.”

This 1946 letter to Bousquet is deeply interested in contesting prevailing cultural norms— whether they be a style of Surrealism Magritte himself helped to create, or language of ‘progress’ in a Europe returning from near fascism.

Importantly, this letter also contains what might be understood as an interpersonal argument. Joë Bousquet himself was a poet and a Surrealist (an original signatory of André Breton’s manifesto). Although Bousquet’s work received little renown during his own life—in part because of his disorienting blend of Surrealist and existentialist prose—today, Bousquet is celebrated. His works were rediscovered in the 1960s by the likes of Simone Weil, Paul Éluard, and Max Ernst. Bousquet’s prose was, in many ways, allied with the disorder of Surrealism—his stories have no plots, and the characters usually appear and disappear by the end of the story. In this way, as Magritte situates this letter as a critique of an artistic movement, he also challenges Bousquet’s own writing.

This letter makes explicit the cultural critique embedded in Magritte’s art— the ethos that made him much more than just “a Surrealist,” but a revolutionary artist and thinker, committed to deconstructing the world around him.

The text (in translation from the original French) reads in full:

“Jette-Brussels, 3rd August 1946

135 rue ESSEGHEM

My dear friend,

Since my departure from Carcassonne, I have written to you on numerous occasions, yet I fear only a handful of my letters have reached you.

Your own missives have been sparse, leaving me with only vague tidings, and your most recent letter has left me unsettled. I await with great impatience the books you promised to send. Your sentiment, expressed long ago, set me on the path I now tread. You spoke of how, by consuming a simple fruit, we let the sunshine enter our bodies.

This notion resonates profoundly with the sentiment that imbues one of my latest works, "La Vie privée" — a painting in which a window overlooking a sun-drenched landscape is nestled within the form of a nude woman. This piece encapsulates the revolution in my art — a sentimental revolution, first and foremost, aimed at replacing anxiety with joy and the warmth of sunshine. The austerity that once defined my style has receded, now more subtle and essential, able to withstand the glare of the midday sun. Is this a demonstration (in the full light of day, we must ponder) of the "results" of a desire to overturn the established order, a desire that the war allowed "men" to indulge for four long years? During that time, I came to believe that these "men" possessed greater means than we did to sow panic, despair, and anxiety from which there was no escape. Yet, paradoxically, these same "men" were utterly bereft of the power to charm. It occurred to me that it is we who hold that power, and if we seek to achieve effects as grandiose as those of evil, but this time in service of good (by which I mean: that which enchants, that which intoxicates), there is much to be reconsidered, discarded, and discovered. To illustrate this notion, I offer two examples: Gallimard's "Série Noire" publishes adventure novels, one of which, "Pas d’orchidées pour Miss Blandish," reaches a certain pinnacle of horror and sickness. I propose the exact opposite, and I believe we have glimpsed this in works such as "Alice in Wonderland" and the tales of Perrault and d’Aulnoy. We must now strive to attain the same power in the realm of the charming and delightful as we do (with such ease) in the realm of the dark and sickening.

"Surrealist” painting, as practiced by numerous artists, has become overwhelming: severed hands abound, blood flows freely, and the inventions are ingeniously disturbing. These artists seem blind, inhabiting a dusty surrealist museum where even a bouquet of real flowers would scandalize. My proposal is to clear this atmosphere, despite the inevitable challenges. Addressing these questions re Le Savoir-Vivre, I say, among other things:

I hate both my own past and that of others

I cherish the laughter of young children running free.”

which illuminates my current sentiments and desires. I am eager to hear your thoughts on these matters. 'Le Savoir-Vivre' is soon to be printed, and I required responses by June 30th. However, timely replies could still be accommodated for publication. (Given the limited space available, please keep your contributions concise). Enclosed is a questionnaire for your convenience.

On the topic of purchases, I enclose a list of items with prices. I'm also sending you a small collection by a young poet – I don't know if you've already received it – and a few illustrated postcards.

I sometimes toy with the idea of surprising you one day, which doesn't seem that utopian to me.

“There’s no such thing as progress — there are good and bad things that are replaced, succeeded and transformed.

There’s nothing to learn — there are things you need to know in order to use them.”

See you soon, I hope, and all the best

Magritte [Signed]

P.S. During the war, did you not receive:

Les Images Défendues by Paul Nougé

Magritte – preface by Marien"

[Translation by Daniele Tort Moloney.]

Autograph Letter Signed [ALS]. Two pages on two sheets (approx. 8.25 x 10.5 in per sheet). Housed in custom presentation folder. Usual mailing folds; fine condition.

AN EXCEPTIONALLY REVEALING AND IMPORTANT LETTER GIVING INSIGHT INTO MAGRITTE'S ART.

References:

- Danchev, Alex. Magritte: A Life. Pantheon, 2021.

- “Joë Bousquet.” EBSCO Research Starters. (Inventory #: 2975)