by CHINESE-CUBAN LABOR CONTRACT

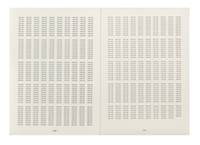

Sheet (318 x 207 mm.), one side printed entirely in Spanish, the other headed in Spanish with terms of indenture in Chinese. Probably China: 1858.

A remarkable survival. “To supplement a dwindling slave labor force on their sugar plantations, Cuban planters turned to south China’s Fujian and especially Guangdong provinces. From 1847 to 1874 they recruited 141,000 male laborers (125,000 of whom arrived in Cuba alive). Slave-like work and living conditions on plantations, with proximity to large numbers of slaves notwithstanding, Chinese coolies were not permanent or lifelong slaves” (Hu-DeHart, “From Slavery to Freedom,” p. 31). Instead, their eight-year employment was governed by Chinese-Spanish bilingual contracts such as these, whose signatories were the Chinese laborers and on-site contracting agents working for firms in Havana. It is also stamped by the Spanish consul in China. “Such contracts testified to the central role taken by the colonial states in organizing, regulating and supervising what was clearly an indenture labor system” (ibid., p. 34).

“The eight years of servitude never varied, nor did the wages of 4 pesos a month. In addition to salary, coolies were paid in food (salt meat, sweet potato or other ‘nutritious vegetables,’ rice, fish), clothing (usually two changes of clothes annually, a wool shirt or jacket, and a blanket), housing, medical attention if sick (but employer may withhold pay or tack extra days on to the original eight years of servitude if sidelined too long). The coolie got three days off during New Year, and Sundays off (except during the harvest in some contracts). The coolie was also advanced a sum of 8 to 14 pesos at time of departure for his passage and for some new clothes, the loan constituting a debt to the patrono to be repaid by deductions from his salary at the rate of 1 peso a month” (ibid., p. 37).

As Evelyn Hu-DeHart shows in her study of these contracts, the framing of indentured labor is different in the Spanish and the Chinese versions, with the former being a formal agreement of emigration (some of them are explicitly titled “Libre Emigración China Para La Isla de Cuba”), while the latter is framed as an overseas work contract (chuyang gongzuo hetong 出洋工作合同), signed at the laborer’s own volition.

This contract is for a Chinese laborer named A-Tao 阿桃 from the province of Fujian, who was around the age of 30. The contracting agent is Manuel Bernabe Pereda. The Chinese side of the contract is signed Xianfeng 7.12.27 (10 Feb. 1858), while the Spanish side is signed 27 March 1858, in Sawtaw (Shantou 汕頭, in Guangdong).

Very good condition. With three folds. The upper portion of the sheet is a little water-stained. Some light foxing and marginal fraying.

❧ Evelyn Hu-DeHart, “From Slavery to Freedom: Chinese Coolies on the Sugar Plantations of Nineteenth Century Cuba,” Labour History 113 (2017), pp. 31–51. Arnold J. Meagher, The Coolie Trade: The Traffic in Chinese Laborers in Latin America, 1847–1874 (Philadelphia: 2008). Juan Pérez de la Riva, Los culíes chinos en Cuba (Havana: Ed. De Ciencias Sociales, 2000). Liza Yun, The Coolie Speaks: Chinese Indentured Laborers and African Slaves in Cuba (Philadelphia: 2008). (Inventory #: 11009)

A remarkable survival. “To supplement a dwindling slave labor force on their sugar plantations, Cuban planters turned to south China’s Fujian and especially Guangdong provinces. From 1847 to 1874 they recruited 141,000 male laborers (125,000 of whom arrived in Cuba alive). Slave-like work and living conditions on plantations, with proximity to large numbers of slaves notwithstanding, Chinese coolies were not permanent or lifelong slaves” (Hu-DeHart, “From Slavery to Freedom,” p. 31). Instead, their eight-year employment was governed by Chinese-Spanish bilingual contracts such as these, whose signatories were the Chinese laborers and on-site contracting agents working for firms in Havana. It is also stamped by the Spanish consul in China. “Such contracts testified to the central role taken by the colonial states in organizing, regulating and supervising what was clearly an indenture labor system” (ibid., p. 34).

“The eight years of servitude never varied, nor did the wages of 4 pesos a month. In addition to salary, coolies were paid in food (salt meat, sweet potato or other ‘nutritious vegetables,’ rice, fish), clothing (usually two changes of clothes annually, a wool shirt or jacket, and a blanket), housing, medical attention if sick (but employer may withhold pay or tack extra days on to the original eight years of servitude if sidelined too long). The coolie got three days off during New Year, and Sundays off (except during the harvest in some contracts). The coolie was also advanced a sum of 8 to 14 pesos at time of departure for his passage and for some new clothes, the loan constituting a debt to the patrono to be repaid by deductions from his salary at the rate of 1 peso a month” (ibid., p. 37).

As Evelyn Hu-DeHart shows in her study of these contracts, the framing of indentured labor is different in the Spanish and the Chinese versions, with the former being a formal agreement of emigration (some of them are explicitly titled “Libre Emigración China Para La Isla de Cuba”), while the latter is framed as an overseas work contract (chuyang gongzuo hetong 出洋工作合同), signed at the laborer’s own volition.

This contract is for a Chinese laborer named A-Tao 阿桃 from the province of Fujian, who was around the age of 30. The contracting agent is Manuel Bernabe Pereda. The Chinese side of the contract is signed Xianfeng 7.12.27 (10 Feb. 1858), while the Spanish side is signed 27 March 1858, in Sawtaw (Shantou 汕頭, in Guangdong).

Very good condition. With three folds. The upper portion of the sheet is a little water-stained. Some light foxing and marginal fraying.

❧ Evelyn Hu-DeHart, “From Slavery to Freedom: Chinese Coolies on the Sugar Plantations of Nineteenth Century Cuba,” Labour History 113 (2017), pp. 31–51. Arnold J. Meagher, The Coolie Trade: The Traffic in Chinese Laborers in Latin America, 1847–1874 (Philadelphia: 2008). Juan Pérez de la Riva, Los culíes chinos en Cuba (Havana: Ed. De Ciencias Sociales, 2000). Liza Yun, The Coolie Speaks: Chinese Indentured Laborers and African Slaves in Cuba (Philadelphia: 2008). (Inventory #: 11009)

![Dainihon meibutsu zukushi 大日本名物尽 [Specialty Products of All the Regions of Japan]](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/772/452/1693452772.0.m.jpg)