by Colgate, James Boorman

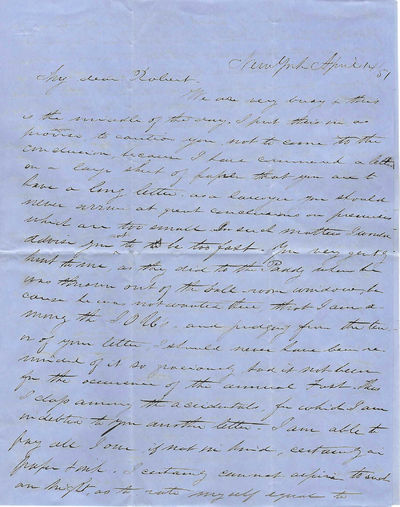

Quarto, 3 pages, plus worn original mailing envelope, letter in very good, clean, and legible condition.

1851 Colgate heir - future Wall Street financier - on the idiosyncrasies of New York (versus Boston) businessmen

"My dear Robert,

…as a lawyer, you should never arrive at great conclusions on premises which are too small…I would advise you not to be too fast. You very gently hint to me, as they did to the Paddy when he was thrown out of the ball-room window, because he was not wanted there, that I am among the I.O.U.s and judging from the tenor of your letter, I should never have been reminded of it so graciously had it not been for the occurrence of the annual Fast…I am able to pay all IOUs, if not in kind, certainly in paper and ink. I certainly cannot aspire to such an height at to rate myself equal to the Hon. Member of East Boston… who cautions our merchants against visiting the good city of Boston and administers such wholesome rebuke for their supposed connivance in disturbing the quiet of the 'Modern Athens', the city of 'isms' – no! no! To assume such a position would be presumption. Our merchants are such boys, especially the Dry Goods, to seem to divert the trade from Boston in such a way and as opportunity occurs I will inform them of what you say and caution them earnestly not to visit Boston for fear of consequences. You have no idea how they will tremble, such information will come among them like a hot shot. The New Yorkers are always fast, though not tight, yet a good many of them like myself are during this month, hard up, in pecuniary matters, having more to pay than they have to pay with. This is often times an awkward dilemma which produces stoppages, suspensions and not infrequently busts and then one is put beyond the stage of hard up and has got as far as used up and then like Micawber of Dickens, he wants to see what will turn up.

With this, I send a letter for Susan which I'll thank you to give her as soon as possible…there is nothing very special in it only she has not heard from me for some time and I have no doubt but that it will be soothing to her feelings 'to learn that I am well and so as to be about' as good old father Peck used to remark. Notwithstanding she is your Sister, I think you will not urge her to stay too long in Boston, as she is needed at home and I should regret if her visit should slightly interfere with those duties you owe to the Commonwealth of Mass…."

The son of Anglo-American soap and toothpaste magnate William Colgate, 33-year-old James had reached a turning-point in his life when he wrote this letter. A month earlier, as a widower, he had married his second wife, Susan Farnum Colby, educator and daughter of a former Governor of New Hampshire, and he was about to leave the venerable Scottish-American New York commercial house in which he had been trained to start his own banking house, dealing in stocks, bonds and, in particular, precious metals. By the time the Civil War began a decade later, he was leader of the New York Gold Exchange, and, after the War, during the financial crisis of the 1870s, his extensive loans to the US Government were instrumental in reestablishing financial confidence in both America and Europe. He was also a major benefactor of Baptist-founded Colgate University, which was later renamed in honor of his family's gifts. (Inventory #: 31259)

1851 Colgate heir - future Wall Street financier - on the idiosyncrasies of New York (versus Boston) businessmen

"My dear Robert,

…as a lawyer, you should never arrive at great conclusions on premises which are too small…I would advise you not to be too fast. You very gently hint to me, as they did to the Paddy when he was thrown out of the ball-room window, because he was not wanted there, that I am among the I.O.U.s and judging from the tenor of your letter, I should never have been reminded of it so graciously had it not been for the occurrence of the annual Fast…I am able to pay all IOUs, if not in kind, certainly in paper and ink. I certainly cannot aspire to such an height at to rate myself equal to the Hon. Member of East Boston… who cautions our merchants against visiting the good city of Boston and administers such wholesome rebuke for their supposed connivance in disturbing the quiet of the 'Modern Athens', the city of 'isms' – no! no! To assume such a position would be presumption. Our merchants are such boys, especially the Dry Goods, to seem to divert the trade from Boston in such a way and as opportunity occurs I will inform them of what you say and caution them earnestly not to visit Boston for fear of consequences. You have no idea how they will tremble, such information will come among them like a hot shot. The New Yorkers are always fast, though not tight, yet a good many of them like myself are during this month, hard up, in pecuniary matters, having more to pay than they have to pay with. This is often times an awkward dilemma which produces stoppages, suspensions and not infrequently busts and then one is put beyond the stage of hard up and has got as far as used up and then like Micawber of Dickens, he wants to see what will turn up.

With this, I send a letter for Susan which I'll thank you to give her as soon as possible…there is nothing very special in it only she has not heard from me for some time and I have no doubt but that it will be soothing to her feelings 'to learn that I am well and so as to be about' as good old father Peck used to remark. Notwithstanding she is your Sister, I think you will not urge her to stay too long in Boston, as she is needed at home and I should regret if her visit should slightly interfere with those duties you owe to the Commonwealth of Mass…."

The son of Anglo-American soap and toothpaste magnate William Colgate, 33-year-old James had reached a turning-point in his life when he wrote this letter. A month earlier, as a widower, he had married his second wife, Susan Farnum Colby, educator and daughter of a former Governor of New Hampshire, and he was about to leave the venerable Scottish-American New York commercial house in which he had been trained to start his own banking house, dealing in stocks, bonds and, in particular, precious metals. By the time the Civil War began a decade later, he was leader of the New York Gold Exchange, and, after the War, during the financial crisis of the 1870s, his extensive loans to the US Government were instrumental in reestablishing financial confidence in both America and Europe. He was also a major benefactor of Baptist-founded Colgate University, which was later renamed in honor of his family's gifts. (Inventory #: 31259)