Hardcover

1733 · Dublin

by CHURCH OF IRELAND

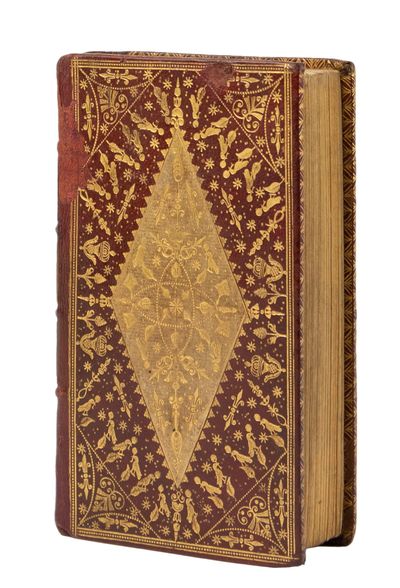

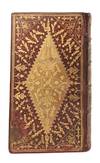

Dublin: Printed by and for George Grierson, printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty, at the King's Arms and Two Bibles in Essex-Street, 1733. With 52 engraved plates on heavier paper, by Elisha Kirkall (1682-1742), printed at London by John Clarke. Hardcover. Fine. An extremely rare Dublin imprint in a contemporary Irish binding. The publisher, George Grierson, husband of the Irish author Constantia Grierson (1705-1732). ESTC locates only 2 copies (British Library, National Library of Ireland.). Bound in ornately tooled contemporary red goat with onlaid cream paper lozenges against a ground richly decorated in gold with birds, feathers, crowned thistles, stars and fleurs-de-lys, divided into compartments with pointillé stipling. Spine with leather onlays in black and citron, elaborately tooled in gold. Board edges and turn-ins also with gilt tooling. Corners lightly bumped, several areas of the boards abraded.

With three tools (bird, fleru-de-lis, star) very similar and possibly identical to Craig, Irish Bookbindings, no. 41 (printed by Grierson’s successor, Boulter, in 1765) See also Maggs catalog 1075, “Bookbinding in the British Isles”, no. 169. However, as Craig notes, “It is quite possible that the Dublin die-sinkers were capable of cutting two or more tools so similar as to deceive all but a scrutiny based on physical proximity of two volumes on which different tools were used.”

“Notwithstanding that white inlays are found in French, Swiss and English bindings before the Irish period, and that there exist contemporary imitations of Irish binding, the popular belief that any binding with a lozenge-shaped white inlay is Irish, is broadly true. Though I know of no non-Parliamentary example before 1737, the binding of Lords 1697 (Plate 1) seems to have had such an inlay. Yet, since Lords 1697 may not have been bound much before 1737, it is possible that the genesis of the style occurred at about that time. The lozenge is one of the few obvious motifs for the decoration of a cover, and was of course exploited in the Grolier period. But it is at least possible that the Irish lozenge is in part a development from the harleian centre-piece. The commonest Irish bindings are Prayer-books of the 1750's, 1760's and 1770's, or almanacks of the 1770's, 1780's and 1790's, of lozenge-inlay type.

“It is convenient to use the term 'inlay', though in fact it seems that no Irish example of a true inlay is known. Strictly, they are all 'overlays'. At least three-quarters of the white or cream examples are of paper. There is no correlation whatever between the richness of the binding and the use of leather in preference to paper. The Royal set of the Statutes, for example, has them in paper, while the Rothschild-National Library set, done for some (inevitably) less exalted personage, has them in leather. In the very finest of the Parliamentary bindings they are usually of paper, as appears from the fact that the wire- and chain-lines emerge clearly in the rubbings. It need hardly be observed that good hand-made paper is, in such a position, capable of being as durable as leather.”(Irish Bookbindings 1600-1800)

The series of prints by Elisha Kirkall (1682-1742) is numbered 1-52. In addition to Biblical scenes, there are three historical prints: “The [Gunpowder] Plot, November 5”, “King Charles I. Murthered”, and “King Charles II, His Return”. The first plate shows King George II and bears the publisher’s information (John Clarke, London). (Inventory #: 4995)

With three tools (bird, fleru-de-lis, star) very similar and possibly identical to Craig, Irish Bookbindings, no. 41 (printed by Grierson’s successor, Boulter, in 1765) See also Maggs catalog 1075, “Bookbinding in the British Isles”, no. 169. However, as Craig notes, “It is quite possible that the Dublin die-sinkers were capable of cutting two or more tools so similar as to deceive all but a scrutiny based on physical proximity of two volumes on which different tools were used.”

“Notwithstanding that white inlays are found in French, Swiss and English bindings before the Irish period, and that there exist contemporary imitations of Irish binding, the popular belief that any binding with a lozenge-shaped white inlay is Irish, is broadly true. Though I know of no non-Parliamentary example before 1737, the binding of Lords 1697 (Plate 1) seems to have had such an inlay. Yet, since Lords 1697 may not have been bound much before 1737, it is possible that the genesis of the style occurred at about that time. The lozenge is one of the few obvious motifs for the decoration of a cover, and was of course exploited in the Grolier period. But it is at least possible that the Irish lozenge is in part a development from the harleian centre-piece. The commonest Irish bindings are Prayer-books of the 1750's, 1760's and 1770's, or almanacks of the 1770's, 1780's and 1790's, of lozenge-inlay type.

“It is convenient to use the term 'inlay', though in fact it seems that no Irish example of a true inlay is known. Strictly, they are all 'overlays'. At least three-quarters of the white or cream examples are of paper. There is no correlation whatever between the richness of the binding and the use of leather in preference to paper. The Royal set of the Statutes, for example, has them in paper, while the Rothschild-National Library set, done for some (inevitably) less exalted personage, has them in leather. In the very finest of the Parliamentary bindings they are usually of paper, as appears from the fact that the wire- and chain-lines emerge clearly in the rubbings. It need hardly be observed that good hand-made paper is, in such a position, capable of being as durable as leather.”(Irish Bookbindings 1600-1800)

The series of prints by Elisha Kirkall (1682-1742) is numbered 1-52. In addition to Biblical scenes, there are three historical prints: “The [Gunpowder] Plot, November 5”, “King Charles I. Murthered”, and “King Charles II, His Return”. The first plate shows King George II and bears the publisher’s information (John Clarke, London). (Inventory #: 4995)

![[Histoire d'Henriette d'Angleterre] Early manuscript copy, in French, of Madame De La Fayette's biography of Henriette d'Angleterre (Henrietta of England), daughter of Charles I of England and sister of Charles II](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/538/756/1693756538.0.m.jpg)