first edition Hardcover

1520 · Basel

by Erasmus, Desiderius (1466?-1536)

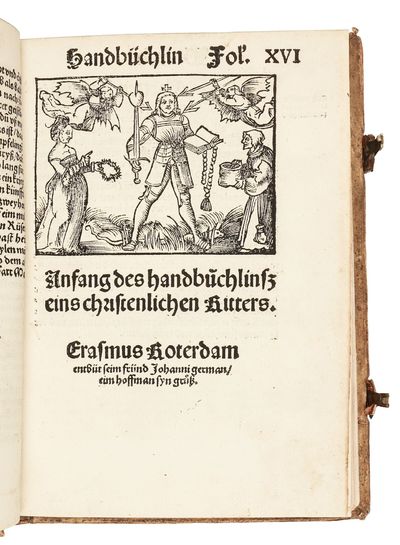

Basel: Adam Petri, March, 1520. FIRST EDITION. Hardcover. Fine. With a four-part woodcut title border, five half-page woodcuts, one of which is repeated, a woodcut printer's mark at the end, and numerous woodcut initials. Bound in contemporary, blind-tooled Augsburg pigskin over wooden boards with two working clasps. Binding soiled and with small stains, otherwise well-preserved. A very good copy. The opening and closing leaves are soiled, the first six leaves have some traces of worming in the margins (backed on two leaves), the last leaf is a little frayed, the inner margin of the title is strengthened with a paper guard; scattered soiling and blemishes. The four woodcuts (one is repeated) and the printer’s device (Heitz-Bernoulli 62) are by Urs Graf (1485-1529); the attractive four-part title border is by Hans Lützelburger -also known as Hans Frank- (d. 1526). The richly tooled binding is probably from the workshop of the Augsburg bookbinder Jeremias Mair. It shows the monogrammed rolls "HK" and "IM” (Haebler I, 232 & 291), which were often used together on the same bindings.

The rare first German edition of one of Erasmus's most widely printed works, “Enchiridion militis christiani” (the handbook of a Christian Knight), a guide to a Christian life, in which he discusses piety, charity, and the study of the Bible, the Church Fathers, and ancient authors. The translator was Johann Adolf Mülich, a native of Strasbourg who had been working as a city physician in Schaffhausen since 1514.

The translation is preceded by a short address to the Reader by the printer Adam Petri and a dedicatory epistle by the translator to The Freiburg nobleman Hans von Schönau, dated 7 December 1519, and a translation of Erasmus’ letter to Paul Volz (Allen Ep. 858). Mülich has also made a free German rendering of Erasmus’ epigram “Libellus loquitur” (The Book Speaks), one of Erasmus' early poems.

The “Enchiridion” was originally published as part of Erasmus’ “Lucubratiunculae”(Little Works written by Lamplight) at Antwerp, in 1503. It was first published separately at Leipzig in 1515. This edition includes Erasmus’ epistle to Paul Volz (1480-1544), dated 14 August, 1518, which has been called “a veritable Erasmian manifesto of the religion of pure spirit.”(Renaudet) The opening poem, “The Book Speaks” is one of Erasmus’ earliest poems:

“I do not care about the praise or the insults of the superficial mob. The fine thing is to please either the learned or the pious. If I happen to do either of these, it is more than I hoped for. If I please someone who relishes the wisdom of Christ, it is well. Christ alone is my Apollo, the source of my vein; his mystic words are my Helicon.”(trans. Mark Vessey)

“The Enchiridion was completed at Louvain in 1502 and was published with several other pieces in February 1503 by Martens. In December 1504 Erasmus sent the entire ‘Lucubratiunculae’ to John Colet with an illuminating personal estimation: ‘The ‘Enchiridion’ I composed not in order to show off my cleverness or style, but solely in order to counteract the error of those who make religion in general consist in rituals and observances of an almost more than Jewish formality, but who are astonishingly indifferent to matters that have to do with true goodness. What I have tried to do, in fact, is to teach a method of morals, as it were, in the manner of those who have originated fixed procedures in the various branches of learning’… Much later, in his famous letter to Dorp in defense of the ‘Moria’, Erasmus reiterates this estimate of his work: ‘In the ‘Enchiridion’ I laid down quite simply the pattern of a Christian life’. (Ep 337:94-5)

“As his book became more widely known, Erasmus expressed his satisfaction with its favorable reception. To Thomas More he recounts with delight: ‘My ‘Enchiridion’ is universally welcome; the bishop of Basel (Cristoph von Utenheim) carries it round with him everywhere -I have seen all the margins marked out in his own hand’ (Ep 412:26-8). Praise came from all sides. In making a list of Erasmus’ works for his brother, Adriaan Barland cites the ‘Enchiridion’ first, ‘a small book of pure gold, and of the greatest use to all those who have determined to abandon the pleasures of the body, to gird up their loins for the life of virtue and make their way to Christ.’(Ep 492:25-8)” (Fantazzi).

“The ‘Enchiridion’ purported to be not only coherent in exposition but also comprehensive in its scope. It did not focus on one problem or aspect of the Christian life, but tried to provide ‘weapons’ that would be useful in whatever circumstances the ‘Christian Soldier’ found himself. It was in its own way a Summa -or, as Erasmus called it, ‘compendiarium quamdam vivendi rationem’- a kind of summary guide to living. Its provisions could of course be amplified, but as it stood it professed to equip its readers with all that was essential to Christian piety, much as Calvin would later claim for his ‘Institutes’, which he in fact terms in the language of his original title a summa pietatis. Like that work, the ‘Enchiridion’ prided itself on the simplicity, yet sufficiency, of what it enjoined.”(O’Malley, Erasmus: Collected Works, Vol. 66). (Inventory #: 5298)

The rare first German edition of one of Erasmus's most widely printed works, “Enchiridion militis christiani” (the handbook of a Christian Knight), a guide to a Christian life, in which he discusses piety, charity, and the study of the Bible, the Church Fathers, and ancient authors. The translator was Johann Adolf Mülich, a native of Strasbourg who had been working as a city physician in Schaffhausen since 1514.

The translation is preceded by a short address to the Reader by the printer Adam Petri and a dedicatory epistle by the translator to The Freiburg nobleman Hans von Schönau, dated 7 December 1519, and a translation of Erasmus’ letter to Paul Volz (Allen Ep. 858). Mülich has also made a free German rendering of Erasmus’ epigram “Libellus loquitur” (The Book Speaks), one of Erasmus' early poems.

The “Enchiridion” was originally published as part of Erasmus’ “Lucubratiunculae”(Little Works written by Lamplight) at Antwerp, in 1503. It was first published separately at Leipzig in 1515. This edition includes Erasmus’ epistle to Paul Volz (1480-1544), dated 14 August, 1518, which has been called “a veritable Erasmian manifesto of the religion of pure spirit.”(Renaudet) The opening poem, “The Book Speaks” is one of Erasmus’ earliest poems:

“I do not care about the praise or the insults of the superficial mob. The fine thing is to please either the learned or the pious. If I happen to do either of these, it is more than I hoped for. If I please someone who relishes the wisdom of Christ, it is well. Christ alone is my Apollo, the source of my vein; his mystic words are my Helicon.”(trans. Mark Vessey)

“The Enchiridion was completed at Louvain in 1502 and was published with several other pieces in February 1503 by Martens. In December 1504 Erasmus sent the entire ‘Lucubratiunculae’ to John Colet with an illuminating personal estimation: ‘The ‘Enchiridion’ I composed not in order to show off my cleverness or style, but solely in order to counteract the error of those who make religion in general consist in rituals and observances of an almost more than Jewish formality, but who are astonishingly indifferent to matters that have to do with true goodness. What I have tried to do, in fact, is to teach a method of morals, as it were, in the manner of those who have originated fixed procedures in the various branches of learning’… Much later, in his famous letter to Dorp in defense of the ‘Moria’, Erasmus reiterates this estimate of his work: ‘In the ‘Enchiridion’ I laid down quite simply the pattern of a Christian life’. (Ep 337:94-5)

“As his book became more widely known, Erasmus expressed his satisfaction with its favorable reception. To Thomas More he recounts with delight: ‘My ‘Enchiridion’ is universally welcome; the bishop of Basel (Cristoph von Utenheim) carries it round with him everywhere -I have seen all the margins marked out in his own hand’ (Ep 412:26-8). Praise came from all sides. In making a list of Erasmus’ works for his brother, Adriaan Barland cites the ‘Enchiridion’ first, ‘a small book of pure gold, and of the greatest use to all those who have determined to abandon the pleasures of the body, to gird up their loins for the life of virtue and make their way to Christ.’(Ep 492:25-8)” (Fantazzi).

“The ‘Enchiridion’ purported to be not only coherent in exposition but also comprehensive in its scope. It did not focus on one problem or aspect of the Christian life, but tried to provide ‘weapons’ that would be useful in whatever circumstances the ‘Christian Soldier’ found himself. It was in its own way a Summa -or, as Erasmus called it, ‘compendiarium quamdam vivendi rationem’- a kind of summary guide to living. Its provisions could of course be amplified, but as it stood it professed to equip its readers with all that was essential to Christian piety, much as Calvin would later claim for his ‘Institutes’, which he in fact terms in the language of his original title a summa pietatis. Like that work, the ‘Enchiridion’ prided itself on the simplicity, yet sufficiency, of what it enjoined.”(O’Malley, Erasmus: Collected Works, Vol. 66). (Inventory #: 5298)

![Polygraphie et universelle écriture cabalistique. Traduicte par Gabriel de Collange, natif de tours en Auvergne. [with:] Clavicule et interpretation sur le contenu és cinq liures de Polygraphie, & vniuerselle escriture cabalistique, traduicte & augmentée par Gabriel de Collange [and:] Tables et figures planispheriques, extensives & dilatatives des recte & anverse, servants à l'uniuverse intelligence de toutes escritures](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/941/108/1694108941.0.m.jpg)