1818 · Florence

by POVERTY — HOMELESSNESS — FLORENCE

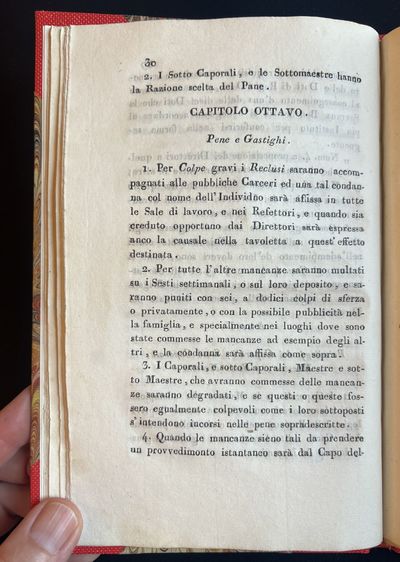

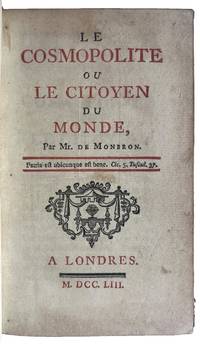

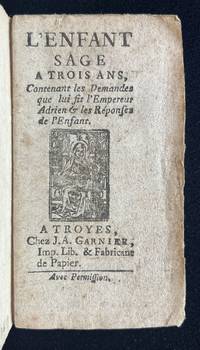

Florence: presso Niccolò Carli, 1818. 8vo (193 x 125 mm). 45, [3 bl.]; 37, [1 bl.] pp. Letterpress tables. The second part is an Appendix, separately paginated, with half-title, and approbation at end dated 1818. (A few small spots to title and last few pages.) Modern half linen and marbled boards, original rear wrapper bound in.***

Only Edition of the rules for the main Florentine workhouse for the destitute, especially for children, established by Napoleon in 1812, to honor the birth of his son the King of Rome, on the site of two former monasteries in the Florentine suburb of Montedomini. The architect Giuseppe del Rosso combined the two monastic edifices, creating one main building in a neoclassical style, and a complex of six smaller buildings for workshops, etc.

The Pia Casa di Montedomini, as it came to be known, was not only a poorhouse, but was a center for poor relief generally. The various categories of candidates for aid are set forth in the introduction: children or adults who were taken in by Montedomini or by other “pious establishments” in the city as permanent residents (known as Reclusi); those who were given work during the day and who returned to their families at the end of the day; those who were given work to carry out at home; and those few who were granted financial help. The Reclusi were divided by age: children under 3 went to the Spedale degli Innocenti, those aged 3 to 10 and 10 to 15 to two different orphanages, and those who were disabled or too old to work to another hospice (Spedale di Bonifazio). Thus families were broken up: this is acknowledged in the text. Blank sample forms are provided for the admission of each category.

Most of the rules are devoted to the main Reclusi, aged 15 and up. The first chapter outlines admissions procedures; chapters 2 and 3 describe their general living conditions and daily routines, and the following chapters address details of work, food, clothing, and bedding, all paid for through the inhabitants’ labor. Not surprisingly, given the Napoleonic inspiration, the Reclusi were organized in quasi-military “brigades,” divided by sex and type of work. The brigades were led by the most compliant and hard-working individuals, male “Caporali” and female “Maestre,” who wore differently colored uniforms from the others. Every moment of the day was strictly regimented, and other than eating and sleeping there was no time for anything other than work, except for two hours of recreation on the occasional special feast day, when only selected individuals were allowed to leave the Casa, in strictly controlled groups.

The daily life of these people, many still basically children, who were imprisoned “for their own good,” is hard to fathom for a modern reader: they rose at 6 or 6:30, prayed, worked until noon, finally were allowed to eat, and then went back to work until 11 or 11:30 pm. Most of the work seems to have involved sewing or needlework; some worked for tailors or other textile workers. Dinner was followed by prayers, and bedtime silence was imposed at 1 am. Meals were spartan: the rations of each ingredient are prescribed down to the ounce. Lunch was 2 ounces of soup, 10 ounces of bread, and 6 ounces of meat or a comparable quantity of vegetables. Dinner was bread and vegetables. One suspects that many barely survived in these conditions.

Other chapters and the Appendix are devoted to the administration of the Casa, accounting and record-keeping, work assignments and payment, and relations with extra-institutional employers.

I locate no copies in American libraries. R. Uccelli, Contributo alla Bibliografia della ToscanaC (1922), 2575. (Inventory #: 4414)

Only Edition of the rules for the main Florentine workhouse for the destitute, especially for children, established by Napoleon in 1812, to honor the birth of his son the King of Rome, on the site of two former monasteries in the Florentine suburb of Montedomini. The architect Giuseppe del Rosso combined the two monastic edifices, creating one main building in a neoclassical style, and a complex of six smaller buildings for workshops, etc.

The Pia Casa di Montedomini, as it came to be known, was not only a poorhouse, but was a center for poor relief generally. The various categories of candidates for aid are set forth in the introduction: children or adults who were taken in by Montedomini or by other “pious establishments” in the city as permanent residents (known as Reclusi); those who were given work during the day and who returned to their families at the end of the day; those who were given work to carry out at home; and those few who were granted financial help. The Reclusi were divided by age: children under 3 went to the Spedale degli Innocenti, those aged 3 to 10 and 10 to 15 to two different orphanages, and those who were disabled or too old to work to another hospice (Spedale di Bonifazio). Thus families were broken up: this is acknowledged in the text. Blank sample forms are provided for the admission of each category.

Most of the rules are devoted to the main Reclusi, aged 15 and up. The first chapter outlines admissions procedures; chapters 2 and 3 describe their general living conditions and daily routines, and the following chapters address details of work, food, clothing, and bedding, all paid for through the inhabitants’ labor. Not surprisingly, given the Napoleonic inspiration, the Reclusi were organized in quasi-military “brigades,” divided by sex and type of work. The brigades were led by the most compliant and hard-working individuals, male “Caporali” and female “Maestre,” who wore differently colored uniforms from the others. Every moment of the day was strictly regimented, and other than eating and sleeping there was no time for anything other than work, except for two hours of recreation on the occasional special feast day, when only selected individuals were allowed to leave the Casa, in strictly controlled groups.

The daily life of these people, many still basically children, who were imprisoned “for their own good,” is hard to fathom for a modern reader: they rose at 6 or 6:30, prayed, worked until noon, finally were allowed to eat, and then went back to work until 11 or 11:30 pm. Most of the work seems to have involved sewing or needlework; some worked for tailors or other textile workers. Dinner was followed by prayers, and bedtime silence was imposed at 1 am. Meals were spartan: the rations of each ingredient are prescribed down to the ounce. Lunch was 2 ounces of soup, 10 ounces of bread, and 6 ounces of meat or a comparable quantity of vegetables. Dinner was bread and vegetables. One suspects that many barely survived in these conditions.

Other chapters and the Appendix are devoted to the administration of the Casa, accounting and record-keeping, work assignments and payment, and relations with extra-institutional employers.

I locate no copies in American libraries. R. Uccelli, Contributo alla Bibliografia della ToscanaC (1922), 2575. (Inventory #: 4414)