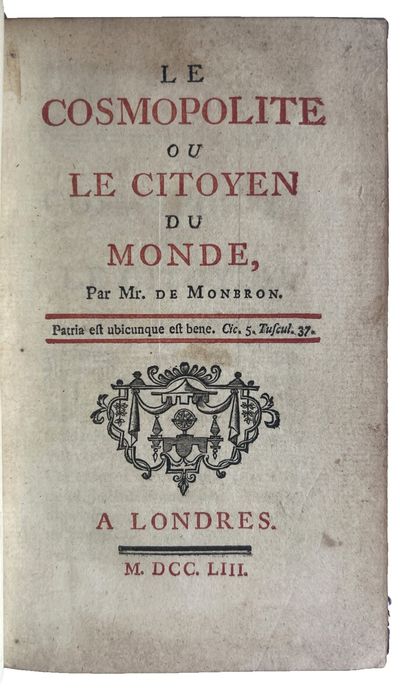

1753 · “A Londres” [probably Paris]

by [FOUGERET DE MONBRON, Louis Charles]

“A Londres” [probably Paris], 1753. 8vo (162 x 98 mm). 165, [3] pp. Title printed in red and black. Type-ornament headpiece and initial border. (Some minor soiling to title, a few small spots.) Contemporary red morocco, covers with triple gilt panels, smooth spine gold-tooled, green morocco gilt longitudinal lettering-piece, edges gilt (spine and extremities scuffed). Provenance: Martine de Béhague, comtesse de Béarn (1870-1939), by descent to her nephew Hubert de Ganay (red ink shelfmarks at end; his? H H bookplate), and thence to his sons, the counts of Ganay.***

A cynical travelogue by a drily funny misanthrope, the Cosmopolite has elicited both laughter and disapproval for almost three centuries. This unclassifiable work’s “impudent and racy attacks on authority” (Broome), and its virulent anticlericalism, earned Fougeret de Monbron (1706-1760) a five-month stay in the Bastille in 1755 (an earlier short stay in a less notorious prison, for his then still unpublished novel Margot la Ravaudeuse, is described in the text).

In his justly celebrated opening paragraph (quoted by Byron, among others), the anonymous narrator states that he used to despise his fatherland (France), but that the idiocies of the inhabitants of the other nations encountered on his travels reconciled him to his birthplace. Visiting Turkey, the Greek Isles, Rome, Naples, the shrine of Loreto (where he stocks up on rosaries and other religious paraphernalia, to be used as tools of seduction), Venice, Florence, other Italian cities, Prussia, Saxony, Spain, Portugal, and England, he makes fun of everything considered admirable or sacred. For example. Rome is the home of a great wizard with a strange tic of constantly whisking two fingers through the air as if chasing flies, whose former sovereignty was challenged two centuries ago by two other “enchanters” named Martin and Jean [Luther and Calvin], and who is now reduced to selling amulets. Leaving to other travel writers practical lists of inns and waystations, as well as learned embellishments and idées reçues that distort the truth of their accounts, the narrator reveals some famous sites as boring, dirty, and disappointing. The ruins and antiquities beloved of contemporaries are often uglier than modern architectural and artistic creations, which have the advantage of not being forged. People are the same everywhere, motivated by self-interest; but the worst are the monks and clerics.

Fougeret’s narrative zest made the work deservedly popular. Demolishing clichés, often at the expense of Frenchmen’s conceptions of their own special talents (for song, gallantry, dress, festivals, etc.), which he shows to be equaled or surpassed elsewhere, he interweaves his observations with autobiographical anecdotes — of the stinky Lazaret in the port of Toulon where those arriving from Turkey had to spend part of their quarantine, and the plague-like disease he picked up there, of his sexual encounters (and mistakes) and bouts with venereal ailments, and of charming conmen like the Italian count, son of an eminent Cardinal, who robbed him blind — and with unorthodox and extremely anti-religious reflections on love, vanity, music, opera, art, and women.

In keeping with his rejection of conventional wisdom, Fougeret’s attitude toward women is unusually empathetic. For example, explaining why the Western European (male’s) vision of available harem beauties is illusory, since the women in Muslim Turkey are locked up, not in delicious gardens, but in plain wood and plaster houses, their shutters permanently closed, he describes these women as “unhappy victims of Eastern jealousy and brutality.” In another indignant passage, treating the Italian celebrations of young women entering their novitiates, the Spose monache, he describes one such event, which he left in tears at the obvious despair of the girl, forced into the convent by “the avarice of her parents” (p.112). A devotee of the prostitutes of all the great cities, he speaks affectionately of their “universally tender and compassionate hearts” (p. 144), which have cost him dearly over the years.

In his famous Henriade Travestie, Fougeret had made fun of Voltaire, but the latter seems to have taken the jibes in stride, and the unproven but generally accepted influence of the Cosmopolite on Candide is probably accurate, although Voltaire never directly mentioned Fougeret in his writings.

First published anonymously in 1750, the Cosmopolite was devoured by the reading public; this is the fourth or fifth edition (all issued under false imprints). The earlier editions are very rare, with two recorded holdings of a 1752 edition in US libraries. This edition was the first to be more widely distributed (11 US copies).

Barbier I: 780; Gay-Lemonnyer I: 740; cf. J. H. Broome, “Voltaire and Fougeret de Monbron a ‘Candide’ Problem Reconsidered,” The Modern Language Review 55, no. 4 (1960): 509–18; and see Édouard Langille’s introduction to the the critical edition of the text (London: Modern Humanities Research Edition, 2010). (Inventory #: 4057a)

A cynical travelogue by a drily funny misanthrope, the Cosmopolite has elicited both laughter and disapproval for almost three centuries. This unclassifiable work’s “impudent and racy attacks on authority” (Broome), and its virulent anticlericalism, earned Fougeret de Monbron (1706-1760) a five-month stay in the Bastille in 1755 (an earlier short stay in a less notorious prison, for his then still unpublished novel Margot la Ravaudeuse, is described in the text).

In his justly celebrated opening paragraph (quoted by Byron, among others), the anonymous narrator states that he used to despise his fatherland (France), but that the idiocies of the inhabitants of the other nations encountered on his travels reconciled him to his birthplace. Visiting Turkey, the Greek Isles, Rome, Naples, the shrine of Loreto (where he stocks up on rosaries and other religious paraphernalia, to be used as tools of seduction), Venice, Florence, other Italian cities, Prussia, Saxony, Spain, Portugal, and England, he makes fun of everything considered admirable or sacred. For example. Rome is the home of a great wizard with a strange tic of constantly whisking two fingers through the air as if chasing flies, whose former sovereignty was challenged two centuries ago by two other “enchanters” named Martin and Jean [Luther and Calvin], and who is now reduced to selling amulets. Leaving to other travel writers practical lists of inns and waystations, as well as learned embellishments and idées reçues that distort the truth of their accounts, the narrator reveals some famous sites as boring, dirty, and disappointing. The ruins and antiquities beloved of contemporaries are often uglier than modern architectural and artistic creations, which have the advantage of not being forged. People are the same everywhere, motivated by self-interest; but the worst are the monks and clerics.

Fougeret’s narrative zest made the work deservedly popular. Demolishing clichés, often at the expense of Frenchmen’s conceptions of their own special talents (for song, gallantry, dress, festivals, etc.), which he shows to be equaled or surpassed elsewhere, he interweaves his observations with autobiographical anecdotes — of the stinky Lazaret in the port of Toulon where those arriving from Turkey had to spend part of their quarantine, and the plague-like disease he picked up there, of his sexual encounters (and mistakes) and bouts with venereal ailments, and of charming conmen like the Italian count, son of an eminent Cardinal, who robbed him blind — and with unorthodox and extremely anti-religious reflections on love, vanity, music, opera, art, and women.

In keeping with his rejection of conventional wisdom, Fougeret’s attitude toward women is unusually empathetic. For example, explaining why the Western European (male’s) vision of available harem beauties is illusory, since the women in Muslim Turkey are locked up, not in delicious gardens, but in plain wood and plaster houses, their shutters permanently closed, he describes these women as “unhappy victims of Eastern jealousy and brutality.” In another indignant passage, treating the Italian celebrations of young women entering their novitiates, the Spose monache, he describes one such event, which he left in tears at the obvious despair of the girl, forced into the convent by “the avarice of her parents” (p.112). A devotee of the prostitutes of all the great cities, he speaks affectionately of their “universally tender and compassionate hearts” (p. 144), which have cost him dearly over the years.

In his famous Henriade Travestie, Fougeret had made fun of Voltaire, but the latter seems to have taken the jibes in stride, and the unproven but generally accepted influence of the Cosmopolite on Candide is probably accurate, although Voltaire never directly mentioned Fougeret in his writings.

First published anonymously in 1750, the Cosmopolite was devoured by the reading public; this is the fourth or fifth edition (all issued under false imprints). The earlier editions are very rare, with two recorded holdings of a 1752 edition in US libraries. This edition was the first to be more widely distributed (11 US copies).

Barbier I: 780; Gay-Lemonnyer I: 740; cf. J. H. Broome, “Voltaire and Fougeret de Monbron a ‘Candide’ Problem Reconsidered,” The Modern Language Review 55, no. 4 (1960): 509–18; and see Édouard Langille’s introduction to the the critical edition of the text (London: Modern Humanities Research Edition, 2010). (Inventory #: 4057a)