1770 · Troyes

by WISE CHILD

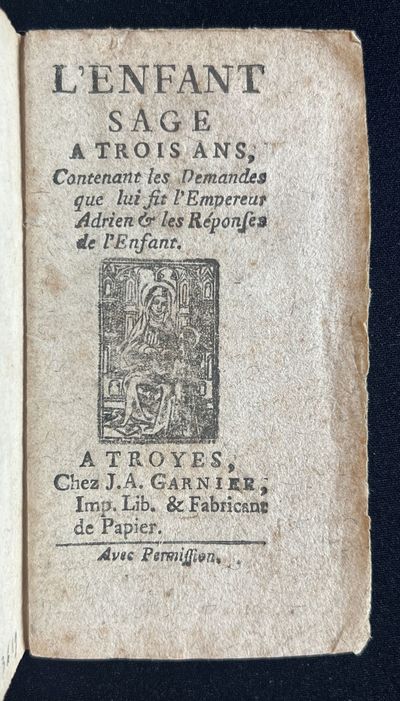

Troyes: Jean-Antoine Garnier, 1770. 24mo (118 x 67 mm). 24 pp. Title woodcut of the Virgin and St. Anne. Untrimmed, in contemporary French block-printed wrappers of floral papier dominoté with pansies, 5-petaled flowers, and closed buds on a dotted ground, printed in black and brown; title and date (1766) written in a 19th-century hand on front cover, back cover with erased Flemish library stamp (last line Flandre-Orientale); tears to backstrip.***

Only Garnier edition of a centuries-old staple of juvenile religious instruction. This pocket chapbook contains the catechism-like dialogue of the Emperor Hadrian and the legendary wise child (Epitus), who answers questions from his pagan elder about religion, Christ, the creation of the world, Biblical figures, death, and redemption. The dialogue is a distant descendant of the Sanskrit and Persian Seven Wise Masters story cycles, via the second-century Roman dialogue between Hadrian and the philosopher Epictetus. Its textual history is complex. Suchier traced eleven different versions (excluding a differently titled Catalan and Hispanic filiation) of a text that had its earliest known incarnation in a late 13th-century Provençal manuscript, and its first surviving printing in Lyon in the 1470s. The 16th-century editions, also “popular” editions, diverge in various ways from the text used in the incunable edition: dubbed by Suchier “ES3,” that version, which borrows also from the Elucidarium of Honorius Augustodunensis, was continuously reprinted, and is that which appears here. It does not represent, as implied by Mandrou, Marais, and others, a reworking of the popular text by a tendentious chapbook editor.

Textual scholars have further traced corruptions and telephone-tag-like mutations of the text through manuscripts and print. Some of those corruptions account for the boy’s more enigmatic responses. While most of his preternaturally enlightened answers embrace standard Christian orthodoxy, others are outright bizarre; e.g., ”What is woman? —The image of death.” This violently misogynistic image, as well as a notoriously anti-Semitic remark, somberly highlighted by Mandrou and other social historians, both turn out to be the result of textual corruptions: The image of death was originally an answer to the question “What is sleep”; the question was missed by a scribe or a compositor and the mistake was perpetuated. Similarly, a remark on Jesus dying for the Jews, who were “bad,” can be traced to a corruption of the word esleuz (élus), or the chosen (people), to ébreus, i.e, Hebrews or Jews (cf. Kleinhans, p. 300).

This was the text’s third appearance in the so-called Bibliothèque bleue, the cheap chapbook editions published in the 17th and 18th centuries in Troyes and other French provincial cities and distributed by colporteurs or peddlers. It was preceded by a 17th-century Troyes edition by the Oudot press, and a Caen edition.

The paper wrappers of this copy are in the style of several examples from Paris and Orléans reproduced by Kopylov and Jammes in their respective volumes on French block-printed paper, but I have not found an exact match.

OCLC locates four copies in American libraries. Morin, Catalogue descriptif de la Bibliothèque Bleue de Troyes 238; Suchier, L’Enfant Sage ... die erhaltenen Versionen (Dresden 1910), pp. 227-228, no. C11; Gumuchian 2410 (misdated ca. 1800). Cf. M. Kleinhans,“`L’Enfant sage à trois ans’ — Vom mittelalterlichen Dialog zum Volksbuch,” Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 106, Heft 3/4 (1990): 289-313; Nisard, Histoire des livres populaires II: pp. 15-17; Mandrou, De la culture populaire aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, La Bibliotheque Bleue de Troyes (Paris 1964), pp. 85-87; J.-L. Marais, “Literature et culture 'populaire' au 17e et 18e siècles,” Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'ouest (1980), 87-1, p. 88. (Inventory #: 4433)

Only Garnier edition of a centuries-old staple of juvenile religious instruction. This pocket chapbook contains the catechism-like dialogue of the Emperor Hadrian and the legendary wise child (Epitus), who answers questions from his pagan elder about religion, Christ, the creation of the world, Biblical figures, death, and redemption. The dialogue is a distant descendant of the Sanskrit and Persian Seven Wise Masters story cycles, via the second-century Roman dialogue between Hadrian and the philosopher Epictetus. Its textual history is complex. Suchier traced eleven different versions (excluding a differently titled Catalan and Hispanic filiation) of a text that had its earliest known incarnation in a late 13th-century Provençal manuscript, and its first surviving printing in Lyon in the 1470s. The 16th-century editions, also “popular” editions, diverge in various ways from the text used in the incunable edition: dubbed by Suchier “ES3,” that version, which borrows also from the Elucidarium of Honorius Augustodunensis, was continuously reprinted, and is that which appears here. It does not represent, as implied by Mandrou, Marais, and others, a reworking of the popular text by a tendentious chapbook editor.

Textual scholars have further traced corruptions and telephone-tag-like mutations of the text through manuscripts and print. Some of those corruptions account for the boy’s more enigmatic responses. While most of his preternaturally enlightened answers embrace standard Christian orthodoxy, others are outright bizarre; e.g., ”What is woman? —The image of death.” This violently misogynistic image, as well as a notoriously anti-Semitic remark, somberly highlighted by Mandrou and other social historians, both turn out to be the result of textual corruptions: The image of death was originally an answer to the question “What is sleep”; the question was missed by a scribe or a compositor and the mistake was perpetuated. Similarly, a remark on Jesus dying for the Jews, who were “bad,” can be traced to a corruption of the word esleuz (élus), or the chosen (people), to ébreus, i.e, Hebrews or Jews (cf. Kleinhans, p. 300).

This was the text’s third appearance in the so-called Bibliothèque bleue, the cheap chapbook editions published in the 17th and 18th centuries in Troyes and other French provincial cities and distributed by colporteurs or peddlers. It was preceded by a 17th-century Troyes edition by the Oudot press, and a Caen edition.

The paper wrappers of this copy are in the style of several examples from Paris and Orléans reproduced by Kopylov and Jammes in their respective volumes on French block-printed paper, but I have not found an exact match.

OCLC locates four copies in American libraries. Morin, Catalogue descriptif de la Bibliothèque Bleue de Troyes 238; Suchier, L’Enfant Sage ... die erhaltenen Versionen (Dresden 1910), pp. 227-228, no. C11; Gumuchian 2410 (misdated ca. 1800). Cf. M. Kleinhans,“`L’Enfant sage à trois ans’ — Vom mittelalterlichen Dialog zum Volksbuch,” Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 106, Heft 3/4 (1990): 289-313; Nisard, Histoire des livres populaires II: pp. 15-17; Mandrou, De la culture populaire aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, La Bibliotheque Bleue de Troyes (Paris 1964), pp. 85-87; J.-L. Marais, “Literature et culture 'populaire' au 17e et 18e siècles,” Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'ouest (1980), 87-1, p. 88. (Inventory #: 4433)